TC#7The meanings of artworks are never fixed; what the artist intends and what the viewer understands may be different. Our individual interpretations of art are rarely the same but shaped by our knowledge, experiences and prejudices.

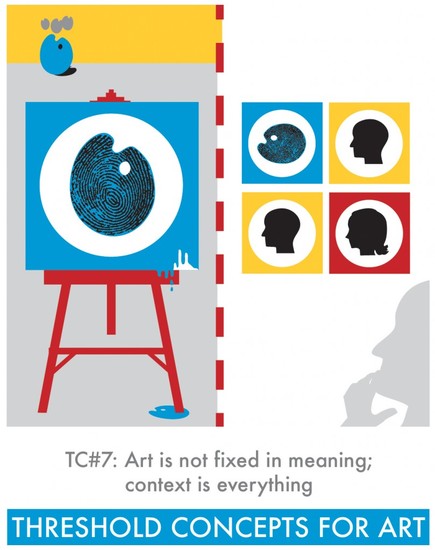

About the graphicOur Threshold Concepts for Art are accompanied with illustrations to aid their introduction. Each image contains a reoccurring graphic: a fingerprint in the shape of an artist's palette. In TC#7 this reoccurs in various forms, each incarnation suggesting new possibilities. To begin, we have a vase of flowers - a traditional Still life, perhaps? In the foreground a canvas displays an artist's response, but this is not quite an accurate representation - the artist has been selective and left their own mark. And then, on the right, we see the work re-presented, rotated, one part of a set of portraits. It re-appears like a face. But what does it mean? I don't understand! Can someone explain? Art is never fixed in meaning. Continue reading for further context...

|

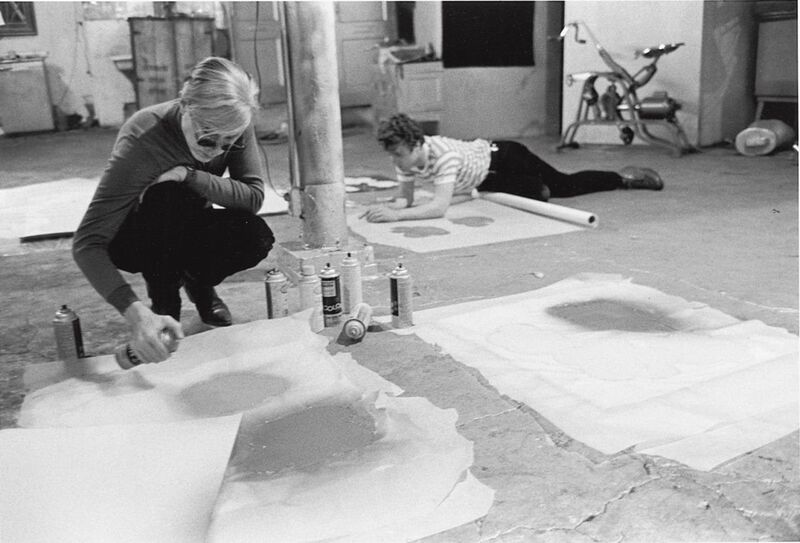

If you’re a baker, making bread, you’re a baker. If you make the best bread in the world, you’re not an artist, but if you bake the bread in the gallery, you’re an artist. So the context makes the difference.

Marina Abramovic

How might the artworks above connect to our TC#7 graphic? How, as pairs of images, might they relate to one another? How does the context of an artwork change when placed alongside another?

WhAT DO I NEED TO KNOW?

- The meanings of artworks are never fixed: Material matters

An artist may set out to produce artwork that means something to themselves, to specific individuals, or perhaps to a broader audience. However, this cannot be guaranteed. The intentions of an artist can be compromised or diverted by the resistance of the materials used - as a result, works of art (and hoped-for meanings) do not always evolve as intended, to good and bad affect. In addition, art materials can be subject to change with time, through handling, wear-and-tear, fading, exposure to the elements etc.; original work can be substituted with reproductions; photographs of artworks inevitably compromise, shrink and abstract originals. Furthermore, our partiality towards certain art materials (and how they are used) is also subject to change, shaped by cultural trends, personal experiences and those in positions of influence such as gallery owners and curators. - The meanings of artworks are never fixed: Subjects and subjectivity

To state some obvious examples: a painting of an individual is likely to hold greater meaning to you if the subject is familiar, say, a close family member; an awareness of 20th Century history might lead you to a greater appreciation of certain art movements (for example, Futurism or Dadaism); a photograph of a landscape is more likely to evoke memories and feelings if you have visited the same location. The subject matter of an artwork - what it is, what it is of, what it represents - is always open to our individual interpretation, shaped by our knowledge, experiences and prejudices. However, what and how we experience is also subject to change. The same painting of a close family member takes on new meaning if that relationship changes; history is rarely fixed - new discoveries and perspectives can radically alter what might have previously seemed secure; memories can rarely be trusted, for example, if recalling a visit to a landscape, memories and emotions can become heightened, diminished, muddled, abstracted, and re-imagined. Not only do our memories influence our experiences of an artwork, but an experience of an artwork can also influence our memory. Art does not only change the way we look at things, it can influence the way we recall the past and imagine the future.

- The meanings of artworks are never fixed: Time and place

Artworks exist as evidence of purposeful action by an artist within a particular time and place. Awareness of this context - when, where, by whom, and why - can influence the meaning that a viewer draws from the work. However, it is rare that artworks are experienced in the time and place of their conception. Artworks are more commonly encountered within a different context, for example, at a future date (where new technologies, ideologies, fashions and concerns might exist) in a different country, perhaps, upon a gallery wall or projected in a lesson, or discovered in a book or via an internet search. Wherever - and whenever - an artwork is encountered, its meaning (to each individual viewer) is subject to change. The environment of this encounter (the surrounding sounds, smells, movements, quality of light etc.), alongside our mood in that moment (our energy levels, worries, social distractions, and so on) will also influence how an artwork impacts upon us. As does, significantly, the decisions of gallery curators, editors, web designers, search-engine algorithms, and so on - all those that, by chance or design, influence the surrounding imagery and words (gallery texts, spoken explanations, themed Pinterest boards etc.).

Below is an introductory slideshow to encourage initial reflections and discussion:

Practical ideas for the classroom

Shifting contexts

- Choose a photograph, painting, poster or small object that you have on display at home. Photograph or sketch this in its original location. Why is it there? How long has it been there for? Who decided it should be in this location? What does it mean to you, and how might the opinions of others in your house differ? Now (and with appropriate permission) relocate this item (or a copy of it) and record it in a variety of new spaces. Try to be as imaginative as possible with alternative locations. What happens when you display it in a public place, perhaps over a period of time? How about within a classroom? Does it provoke new questions or discussions, and if so what kind of things are said? Does the item seem more (or less) interesting, or perhaps more absurd or profound, when 'out of context'? How do you now feel about it - has its meaning changed (for you, or others)?

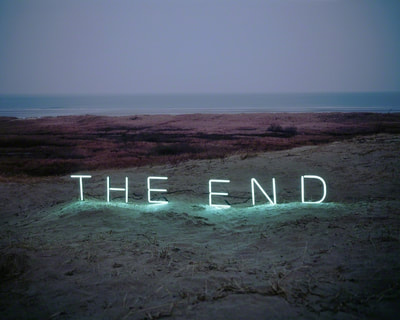

- Many artists have been drawn to creating or exhibiting artwork in unexpected locations. It might be suggested that this has always been the case - artworks were created on bodies, caves and tombs (for example), long before the emergence of studios or galleries. Artists often produce or install work in unusual locations to create unusual contrasts that disrupt expectations. These types of work are often described as 'interventions' and can take any form, from paintings or sculptures, to projections and performances. Below are some examples, from the playful and visually appealing to the politically motivated. Click on the links for further information. Use these as inspiration to produce your own artistic 'interventions' that may contrast or conflict with their environment.

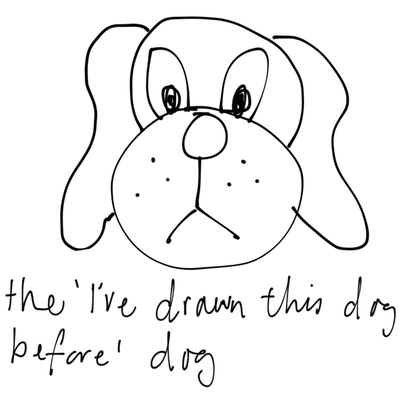

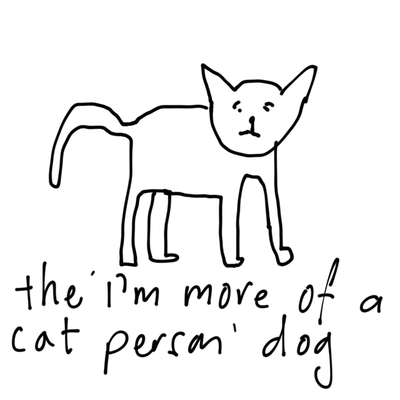

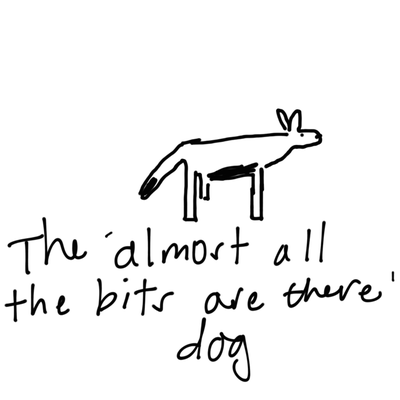

How predictable

- What happens when a group of people respond creatively to the same set of instructions? How might their responses differ, and why? For example, deliver these instructions to a class: In 1 minute only, draw a DOG. How accurately could you predict or even replicate the results prior to completion? Write a list of factors that might influence any significant differences, for example: the type of materials used (for example, pencil, paintbrush, felt tip etc.; also the size of paper provided); whether they own a dog or not (could this really have a bearing - for example, are they more likely to draw a specific breed?); the age of the person; whether they draw regularly etc.

- What happens when a more abstract concept is introduced e.g. flip the letters of 'DOG' around and instruct: In 1 minute only, draw a GOD. How does this now complicate the task? What experiences, beliefs, skills or intentions now come into play? What makes one person thrive with a particular challenge while others may struggle or flounder?

- Devise a clear set of simple instructions for a group to respond to, choose something that is likely to reveal personal interpretations, tastes or biases.

Iconic, ironic

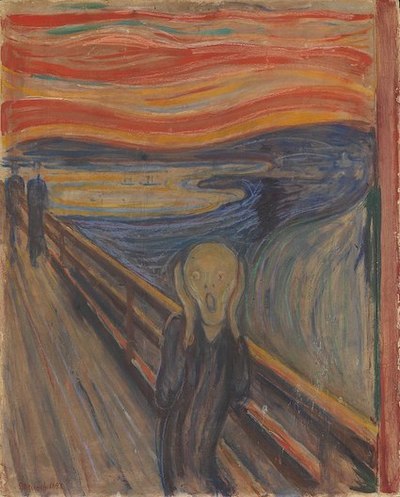

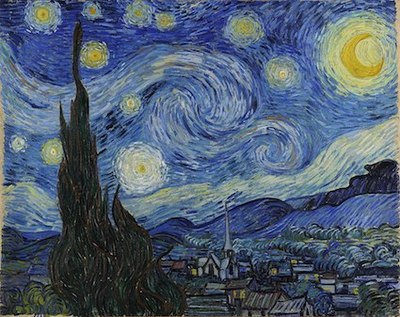

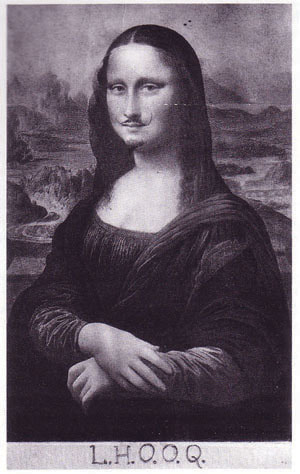

There are certain artworks (and artists) that for various reasons (and not always appropriately) are often described as 'iconic'. What is usually meant is that the artwork (or artist) has become so famous that it seems to be representative of something bigger, way beyond its surface materials and subject matter - perhaps representative of a particular art movement, another period in time, or a set of beliefs or state of being.

Look at the examples below and consider the following prompts: Which artworks are immediately familiar to you? Do you know the name of each artwork and artist? What do these works of art mean to you? Why might they hold great significance to others? What might they represent? Click on each image to find out more.

There are certain artworks (and artists) that for various reasons (and not always appropriately) are often described as 'iconic'. What is usually meant is that the artwork (or artist) has become so famous that it seems to be representative of something bigger, way beyond its surface materials and subject matter - perhaps representative of a particular art movement, another period in time, or a set of beliefs or state of being.

Look at the examples below and consider the following prompts: Which artworks are immediately familiar to you? Do you know the name of each artwork and artist? What do these works of art mean to you? Why might they hold great significance to others? What might they represent? Click on each image to find out more.

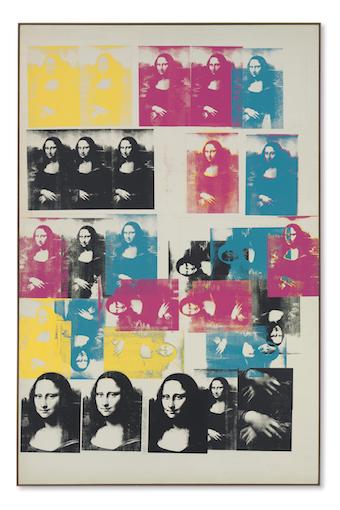

As with meanings, the status of these artworks remains subject to change. New generations will find alternative representations for their own desires, anxieties and states of being, and these, in turn, will likely be shared, appropriated, parodied, and reconsidered (until they represent something else, and/or become considered too twee or kitsch, for or art educators, for example).

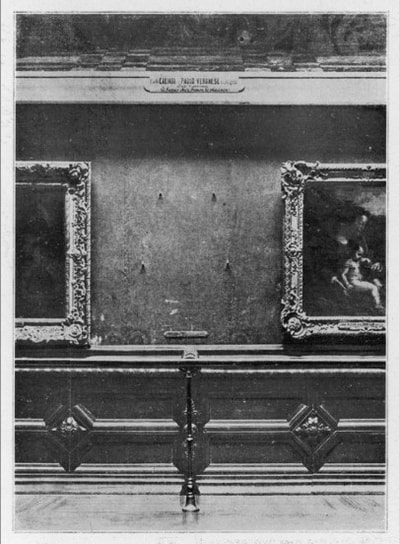

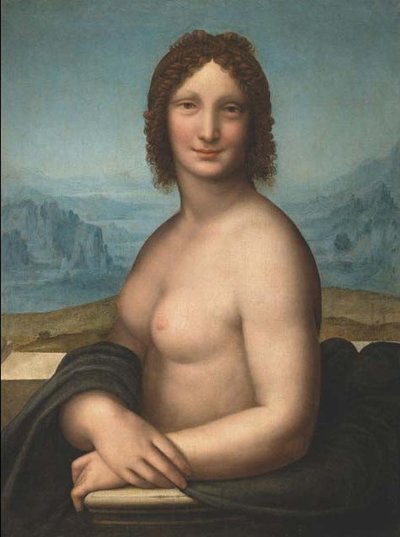

Below are a range of images and prompts to help provoke discussion on various contexts regarding the iconic status of the Mona Lisa. (Whether the focus on the Mona Lisa here is ironic in itself, I'm uncertain, such is the rabbit-hole of our post-modern condition). Regardless, links are provided to add further context. TC#4, artists use and abuse traditions is also particularly relevant here.

Below are a range of images and prompts to help provoke discussion on various contexts regarding the iconic status of the Mona Lisa. (Whether the focus on the Mona Lisa here is ironic in itself, I'm uncertain, such is the rabbit-hole of our post-modern condition). Regardless, links are provided to add further context. TC#4, artists use and abuse traditions is also particularly relevant here.

“A shame that these images had become iconic, a tune we were all tired of humming.”

Elizabeth Kostova

- How does an artwork become so... well-known, famous, infamous, notorious, iconic, ironic, sought-after, hated, expensive, precious, devalued, boring..?

- The Mona Lisa is estimated to have been painted in 1503. Upon completion was the work actively promoted? If so, who did this, why and how?

- What would those directly involved in its creation - Leonardo Da Vinci, the artist, the model, Lisa del Giocondo, and her husband Francesco del Gioconda, who commissioned the work - think of its status today?

- What events, through chance or intention, have led to the Mona Lisa's iconic status, and which people have been most significant in this? For example, is Vincenzo Peruggia more responsible for its fame than, say, Karl Baedeker?

- Consider the length of time and sequence of events that has led to the Mona Lisa becoming so well-known. Is this type of slow-cooked fame possible today? How does our 24 hour news culture, the internet, social media etc. influence the way we notice and think about artworks and what they might mean to us?

"Art history is a global version of that old children's game Chinese whispers.”

Grayson Perry

FURTHER READING

The following texts have been chosen to promote wider contextual study. Students should consider the author's intentions, their chosen writing style, and how the texts combine research and historical facts alongside personal insights and opinions.

- The artwork that made me the most dangerous person in China, Ai Weiwei, The Guardian, 2018

- American Beauty - Andy Warhol, Jonathan Jones, The Guardian, 2002

- Pussy Riot + The Russian Orthodox Church..., Scott MacDougall, Huffington Post, 2013

- Why is the Mona Lisa so famous? Alicja Zelazko, Encyclopedia Britannica