TC#2Art, in many forms, tells us of our past, present and future, shaping and influencing our lives in significant ways. However, Art is not dependent on language or logic; it has the capacity to communicate directly with our nervous systems.

About the graphicOur Threshold Concepts for Art are accompanied with illustrations to aid their introduction. Each image contains a reoccurring graphic: a fingerprint in the shape of an artist's palette. In TC#2, the palette also represents four of our five senses - sight, taste, smell, hearing - accompanied by a hand for touch. Additionally, it is a beating red heart, suggesting the importance of art's affective power, its ability to move us and remind us of our shared humanity. Artists, critics, art teachers and art historians use language all the time to share their love of the subject. But art makes its own sense too. It is its own special language that often communicates directly with our bodies.

|

“ColoUr is the keyboard, the eyes are the harmonies, the soul is the piano with many strings. The artist is the hand that plays, touching one key or another, to cause vibrations in the soul.”

WASSILY KANDINSKY

How might the artworks above connect to our TC#2 graphic? Follow the links to find out more. Do these 3 artworks share common methods of communication? Which example of work communicates the most to you? What is its appeal and why?

WhAT DO I NEED TO KNOW?

- Art tells us of our past, present and future. Art history continually informs - communicates with - the art that we now make, experience and imagine. Art 'histories' is a better description than 'art history': there is not one simple (hi)story although some narratives (including particular artists and art movements) can dominate.

- Some people think that the first kind of 'art' made by humans was probably a kind of performance in which people painted their bodies with natural pigments and danced together, perhaps related to a primitive hunting ritual. This was before anyone had the idea of painting bisons on cave walls. Although prehistoric and ancient 'art' wasn't really like the art we know and experience today, humans have always attempted to communicate the products of their imaginations in a variety of forms.

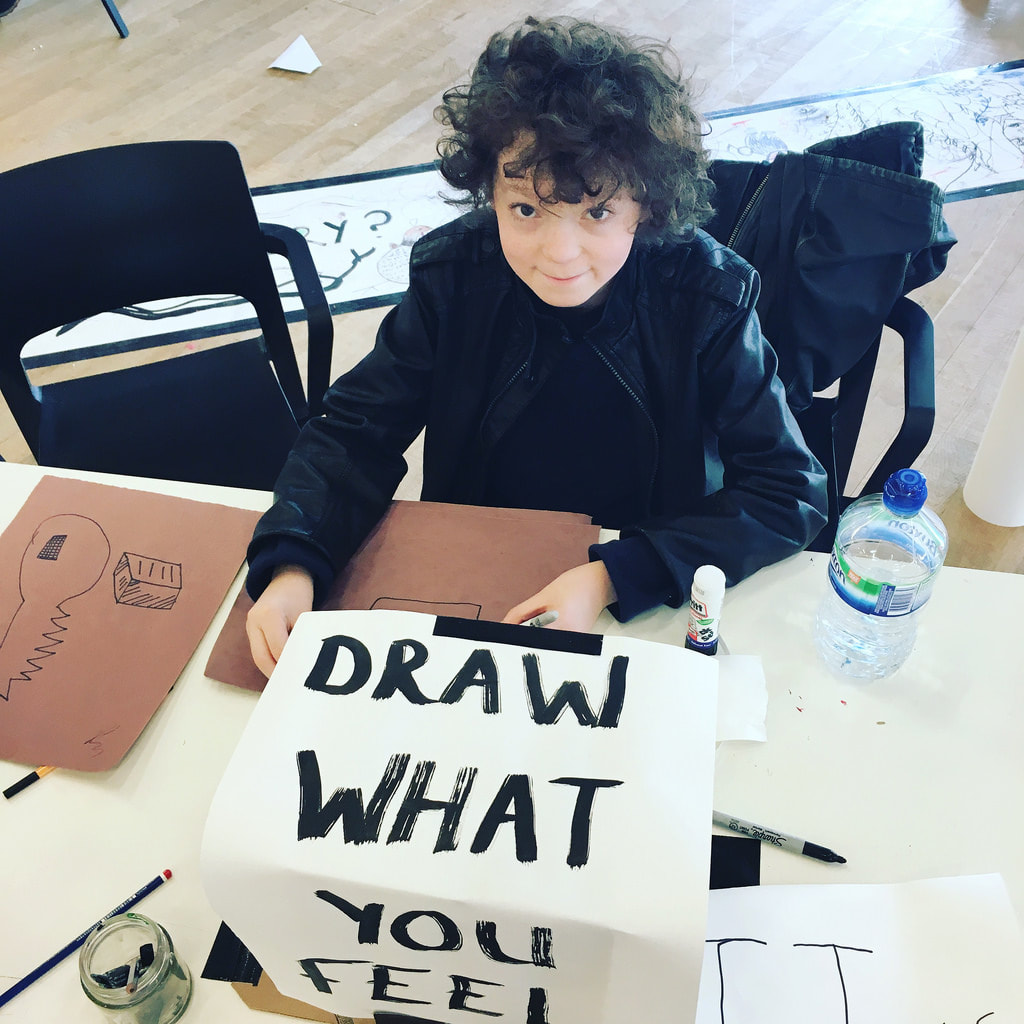

- Our ability to communicate through and with art is not fixed or limited but subject to change with age and experience, for good and bad. Remember when you were a small child, before you could speak or use words. What kind of art did you make? What materials did you use? Why did you do it? How did it make you feel? As we grow older and learn to communicate with words, the type of art that we make and the reasons we do so are subject to change.

- We are sophisticated users of language. For most of us, words are the main way we communicate with one another. Sometimes it's easy to forget that art has a language of its own that doesn't always rely on words to make sense. When we make and experience art we need to use all of our senses (not just our eyes) plus our feelings and intuitions. Art should make us think, using our brains and language to puzzle and ponder. But we shouldn't neglect the rest of our bodies. We need head, heart and hands to get the most out of our experience of art. It is not always easy to put into words how art can make us feel.

Below is an introductory slideshow to encourage initial reflections and discussion:

Practical ideas for the classroom

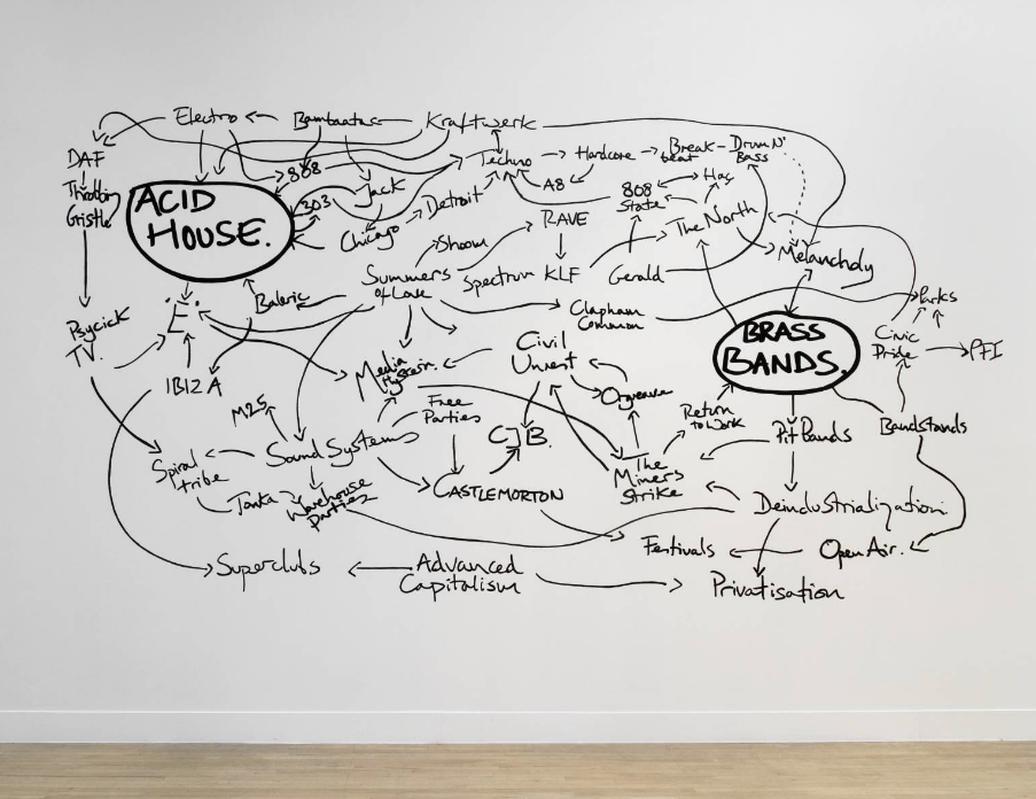

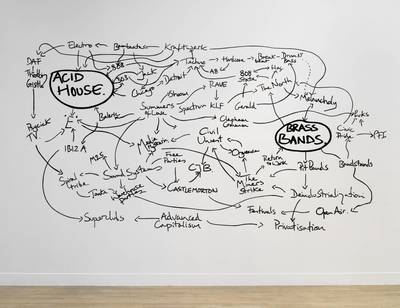

- Take a look at Jeremy Deller's 'The History of the World'. Deller's wall drawing looks like a mindmap. The terms 'Acid House' and 'Brass Bands' are circled and a tangled web of lines and arrows connects them together, demonstrating that they are linked by lots of other cultural, social and political phenomena. Ask the students to undertake some research linking two seemingly different art works. For example, how can we connect Picasso's 'Les Demoiselles d'Avignon' to Poussin's 'A Dance to the Music of Time'? The idea is to encourage the students to be inquisitive, to behave like art detectives trying to piece together significant clues, to show that all works of art are, in various ways, connected to all other works of art.

|

|

- Art can have a powerful effect on us that we can't always easily explain. Arrange a selection of reproductions of works of art (as varied as possible) around the room. Ask students to view them, deciding quite quickly which art works attract them and which do not. Encourage them not to think about this too much. What is their immediate reaction, even before they have begun to put this into words (NB. this is sometimes referred to as "Affect"). Ask them to stand nearest the work that they were most drawn to. Look around the room. What do you and they notice? Now repeat for the works that students were most repelled by. What happens? NB. This activity also works really well in museums and galleries. Students could be encouraged to keep a note of the artworks they drawn to and repelled from. This might make an interesting drawing/mapping activity too.

|

|

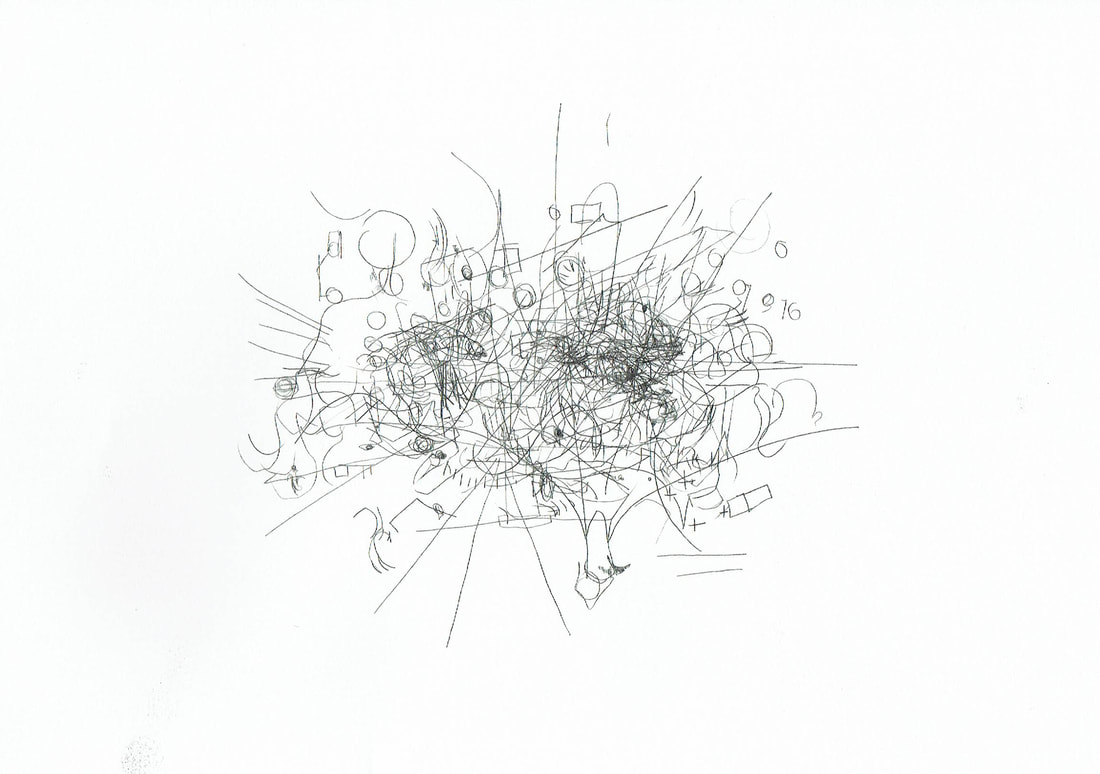

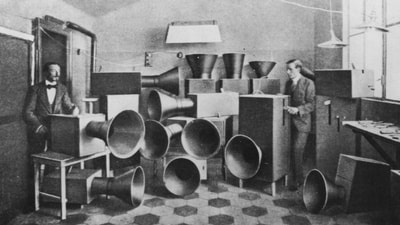

- Explore the relationship between visual art and sound. Kandinsky, for example, is thought to have experienced synaesthesia. He heard colours as if they were particular qualities of sound. Play a piece of music to students and ask them to draw/paint/model their response. You could also share examples of works of art with musical titles (for example by Kandinsky, Klee, Whistler, Hoyland, Pasmore) and ask students to describe (or even perform) the sounds suggested.

- Explore the relationship between touch and sight through 'blind' drawing. For example, you could place a variety of objects in a cardboard box with a hole cut in the side big enough to insert one hand. Students can only feel the object(s) inside, using the information from their sense of touch to draw whatever they can feel. The artist Anna Lucas has created Blind Movie drawings using carbon paper. She watches a film and draws the way her eyes move across the screen. These continuous line drawings, made without looking down at the paper, document long periods of continuous looking as abstract drawings.

it has been and will always be the function of the arts to make three contributions to our lives. The first is that the arts provide a means through which meanings that are ineffable can be expressed [...] Second, the arts afford opportunities for individuals to use and develop their minds in distinctive ways through learning to think within a medium whose unique and special messages are conveyed in sound, sight, or movemenT [...] Third, the arts make possible a certain quality of experience we call aesthetic. Aesthetic forms of experience are memorable.

Elliot w. Eisner

"A work of art is a world in itself reflecting senses and emotions of the artist's world."

Hans Hofmann

FURTHER READING

The following texts have been chosen to promote wider contextual study. Students should consider the author's intentions, their chosen writing style, and how the texts combine research and historical facts alongside personal insights and opinions.

- Kandinsky on the Spiritual Element in Art and the Three Responsibilities of Artists

- Art for the Senses, part of Tate's Sensorium project

- How synaesthesia inspires artists

- The Power to Look, Khan Academy