TC#1 LESSON RESOURCE: PREHISTORY NOW

“Man began to make images only because he discovered them nearly fully formed around him, already within reach. He saw them in a bone, in the bumps of a cave, in a piece of wood. One form suggested a woman, another a buffalo, the head of a monster...we have returned to prehistoric times...” BRASSaï

ABOUTThis resource is in support of Threshold Concept 1: Artists make marks, drawing our attention. You can read the 'big ideas' relating to this concept here. It also links most directly to TC#2, TC#3, TC#6 and TC#7. The insights and activities are aimed at KS4 and KS5 students but are easily adaptable for other age groups.

THEMESInspiration for this resource stems from a visit to Prehistory - A Modern Enigma, an exhibition at the Centre Pompidou, Paris, 2019. The exhibition highlights the influence of 'Prehistory' on artists, in particular at the beginning of the 2oth Century when new discoveries of Cave Art came to light.

A key aim of this resource is to promote thinking about the kind of marks we make and why, in relation to the work of others but also in relation to the natural world and our connections (and disconnections) with this. In addition, this resource aims to encourage some deeper digging - beyond the popular appeal of what is often disingenuously-labelled primitive art - to expose murky issues of cultural appropriation and western, colonial, assumptions. The practical activities are designed to channel this critical thinking whilst promoting experimentation and collaboration, inside and outside the art room. |

The most exact scientific knowledge of nature, plants, animals, the earth and its history, and the stars, is of no use if we are not equipped for its representation. Paul Klee

FOR DISCUSSION

- What kind of marks, imagery and artefacts were created by the first humans? Where were these created and for what purpose?

- From the late 1800s until the present-day, how have artists responded to Prehistorical art - and why?

- What might Prehistorical Art - and subsequent artistic responses to this - tell us about our past, present, or even our future?

- Why are some artists drawn towards seemingly 'primitive' approaches and techniques - ways of working that appear less realistic or representational; more expressive, symbolic or abstracted?

- Why are art terms such as 'Primitive' and 'Primitivism' problematic? What assumptions and injustices have arisen from the discovery of prehistoric Art? How have these evolved, and how should they now be addressed?

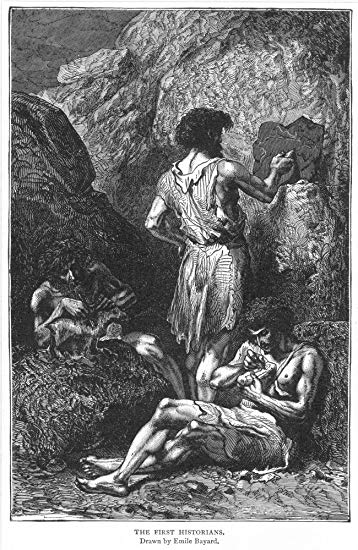

The first image, above left, is an engraving titled "The First Historians," drawn by Emile Bayard. The scene depicts three prehistoric men recording the shape of a deer in three different ways: carving it, etching it on a rock wall, and shaping a clay figure. It might be considered an illustration. The second image is a sculpture by Picasso using found materials - from a gas cooker. This form is clearly influenced by primitive sculptures such as Paleolithic fertility statues. The third image is a photograph by Brassaï, of wall markings in Paris, taken in the mid 1900s. He produced a large series of these 'Graffiti' images, comparable to images of prehistoric art widely publicised at that time. A Joan Miró painting is the final image - Miró's work is often described as childlike, abstract, surreal or primitive. Miró sought a more direct, instinctive way of working, one disruptive of the conventional painting methods of his time.

WHAT DO I NEED TO KNOW?

- The examples of art, above, created in the 20th Century, reference early forms of art making by humans. This 'knowingness' - the awareness and suggestion of art made thousands of years before - might be described as 'reverential', 'in respect of' - or even 'playful', 'ironic' or '(Post)modern'. From the end of the 19th Century to the midpoint of the 20th Century (a period known as Modernism) there was a surge in creative responses and thinking influenced by 'Prehistory' and related discoveries.

- "Prehistory" is a modern idea. The word was coined in the 1860s and refers to the emergence of human beings. The development of technology and science in the 1800s; advancements in analysing and dating rocks; the astounding discoveries of cave art in Northern Europe; a series of influential exhibitions in museums of Paris, New York and London - these all led to a deep fascination with 'Prehistory' for artists of this period.

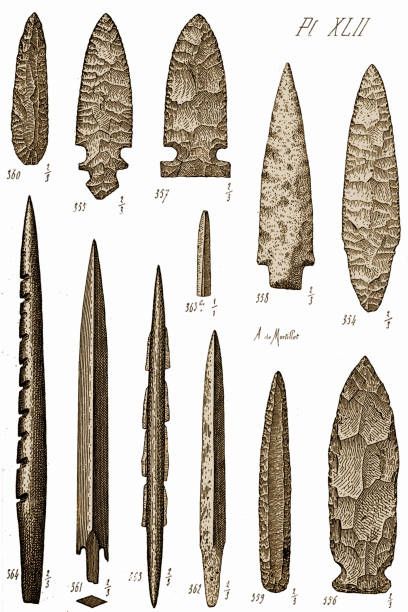

- Some of the earliest figurative art created by Homo sapiens is to be found within caves on the island of Sulawesi, Indonesia. The oldest examples of art have been dated as at least 35,400 years old and include hand-stencils and ochre and charcoal drawings of animals. It is believed that marks were made through drawing, brushing, smearing, dabbing, and spraying (spitting and blowing). Sticks, fingers, animal bones and brushes made from horsehair may have all been used to create art. Large areas of colouring may have been covered with fingertips or pads of lichen or moss. Some of the earliest sculpted forms include arrow heads, engraved surfaces and figurines.

- A growing realisation that the earth was once unpopulated and that humans had gradually evolved over thousands and thousands of years led to radical new perspectives of thought - not just regarding the past, but also the future. The industrial Revolution had marked a dramatic transition in humankind's relationship with the environment - not least in a shift from farming communities to industrialised towns and cities; the First (and subsequently Second) World War led to a surge in machine and manufacturing technologies; the consequent programmes of post-war reconstruction saw the embracing of new building materials and styles. Artists of this time - most significantly in Europe, many ostracised and disillusioned with the state of the world (including the art world) - turned to Prehistoric Art for inspiration and understanding.

- The language and attitudes connected with ‘primitivism’ and the word ‘primitive’ are problematic. Late 19th and early 20th century interests in pre-historic, non-Western, pre-Christian, ‘exotic' art from Africa and Oceania, were driven by colonialism. It was a form of cultural appropriation. It may be that the artists admired these artefacts, but they didn’t neccesarily make much effort to understand them in their original contexts. The creation of 'museums of mankind' to house artworks and artefacts (often stolen) betrays the sexist and racist attitudes of the time. The qualities the artists saw in the objects might be critically considered reflective of patronising, western, colonialist assumptions.

- Prehistoric Art is often attributed to 'early man' or 'primitive' or 'prehistoric man'. Prehistoric people - men and women - probably used 'mark-making' in lots of other ways that haven’t survived - such as body painting, sound/music and dance/performance. Women may well have been originators of ‘culture’, and early human groups matriarchal. Patriarchal societies and systems have shaped the telling of history.

- Artists were - are still - drawn to Prehistoric and 'Primitive' Art for many reasons: as an antidote to the established status-quo, for example in the art world e.g. a tendency towards Romanticism and Realism in the early 1900s) ; for its material and sensory (re)connection with nature and the use of of earth-made materials upon natural surfaces; the tactile experience of direct mark making; the quest for a more earthly or spiritual connection, the sacred, spiritual, ritual and symbolic; the visual appeal of primitive art as a means of abstraction and alternative representation.

- The discovery of Cave Art and artefacts from across different continents, including Europe, Africa, South America, Australasia and Asia, revealed Prehistoric human (at various stages of evolution - Paleolithic Period, Mesolithic Period, and Neolithic Period) as skilled, resourceful, resilient and creative - far from 'primitive' in an unintelligent sense. Many cave paintings are highly difficult to access, deep below ground or set in inaccessible cliff-faces. Why early humans began to produce Art, and where they did too, has been the subject of much speculation - potentially for reasons of ritual, worship, communication, decoration, entertainment, expression or something more practical - for example, ochre is considered a mosquito repellant; some cave markings appear to map movements of tide, moon, menstrual cycles or animal herds. What is known is that a deep connection to nature and awareness of its seasons, offerings and dangers - to hunt, eat, procreate and survive, often in extreme cold or heat - was essential.

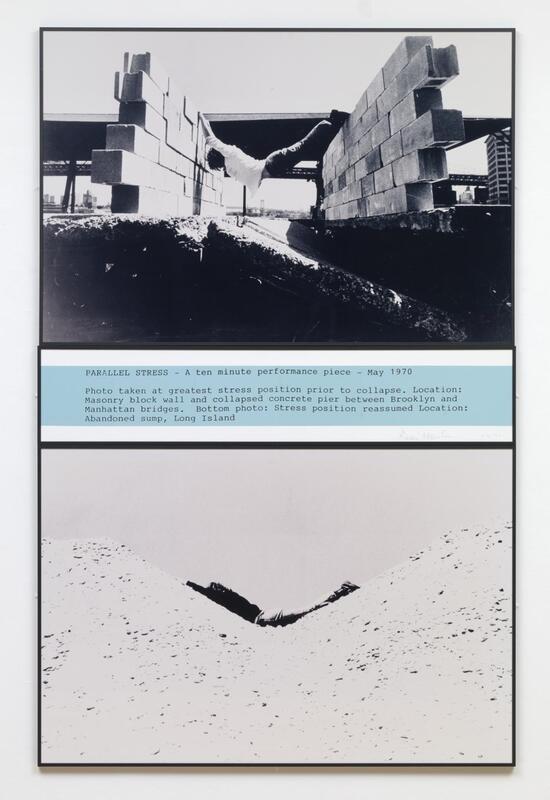

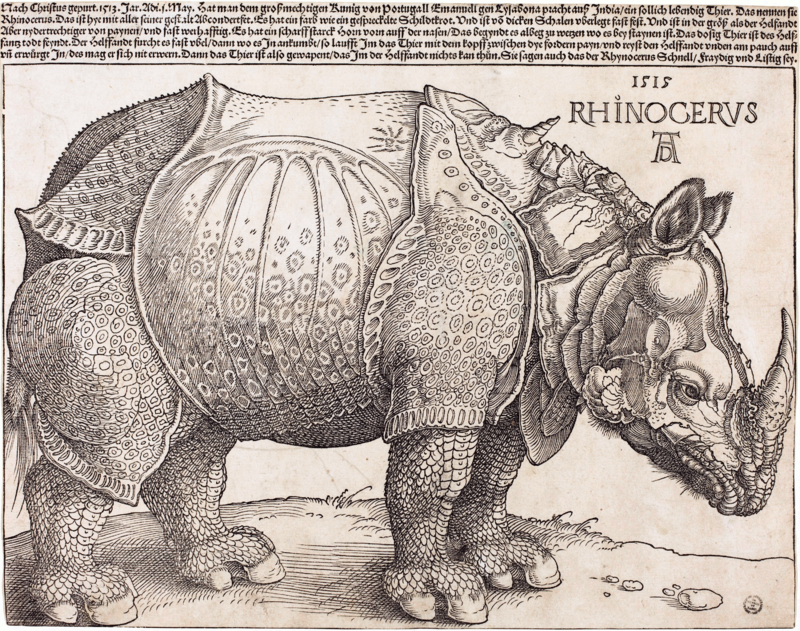

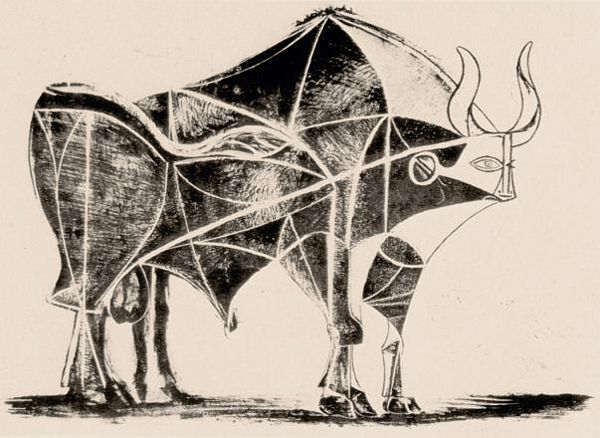

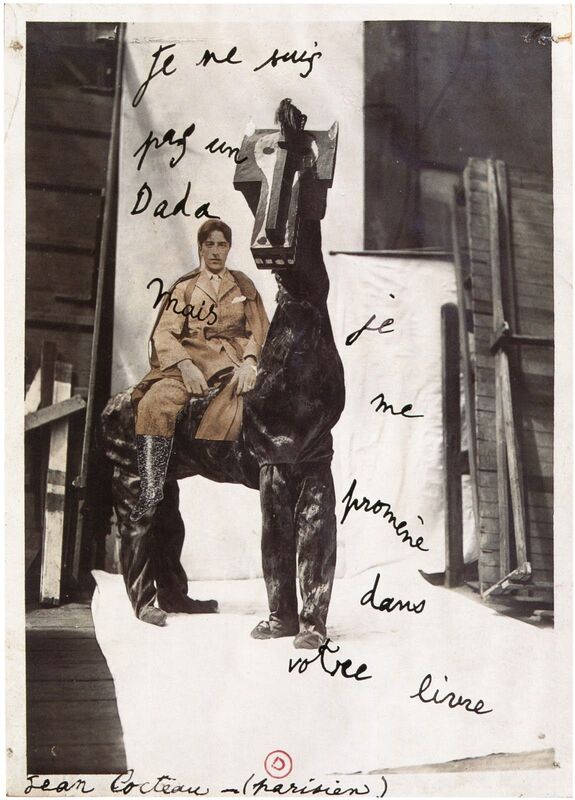

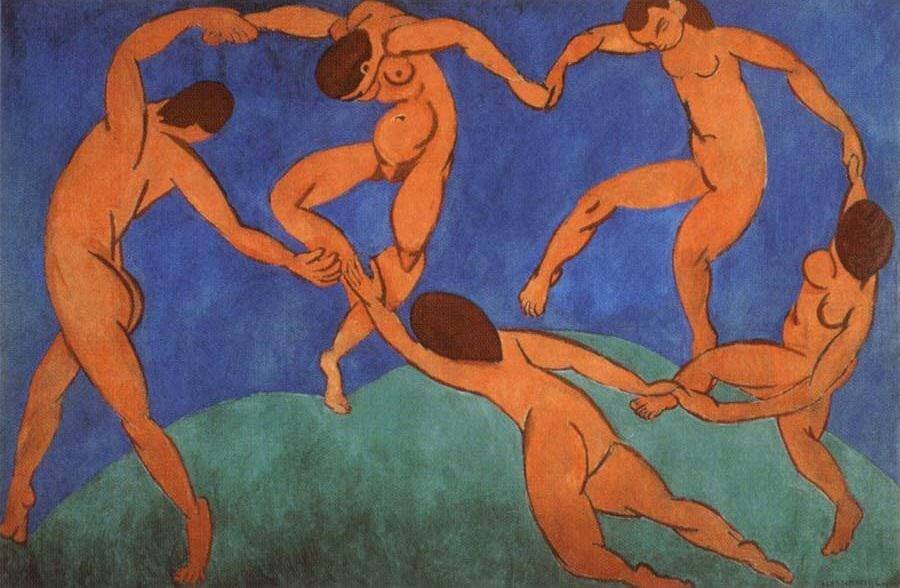

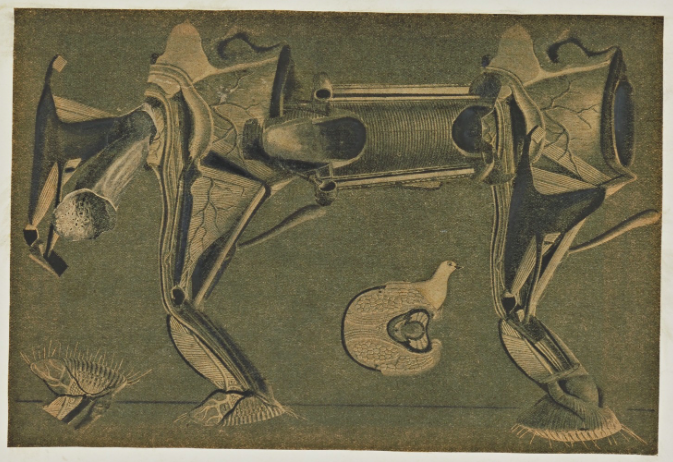

The images above show a range of artworks that demonstrate the influence of the prehistoric on a diverse collection of artists, from the mid 1800s to more recently. These responses vary in greatly in visual, technical, contextual and conceptual values. Click on the images to see larger versions. Research the artists/titles to find out more. Is it possible to date and order these chronologically without reference to the text? Which work resonates most with you? What do you consider the most skilled, expressive, poignant, playful, authentic?

Practical ideas for the classroom

Actions & Tools

How resourceful would you be if left to make art, outside, without any art materials? What might our environment (natural or man-made) offer in terms of potential materials, and to what effect (and affect)? - What are the limitations, possibilities, affordances and resistance of potential materials? How have other artists responded to this challenge, and what might we learn from their work?

How resourceful would you be if left to make art, outside, without any art materials? What might our environment (natural or man-made) offer in terms of potential materials, and to what effect (and affect)? - What are the limitations, possibilities, affordances and resistance of potential materials? How have other artists responded to this challenge, and what might we learn from their work?

WE ARE INCREASINGLY separated from contact with nature. we have come to forget that our minds are shaped by the bodily experience of being in the world - its spaces, textures, sounds, smells and habits [...] we are literally 'losing touch', becoming disembodied, more than in Any historical period before ours.

ROBERT Macfarlane

- Identify an area outside, ideally (but not necessarily) containing elements of nature. This might be a garden, a section of school grounds or a public park. What found materials are available to create art?

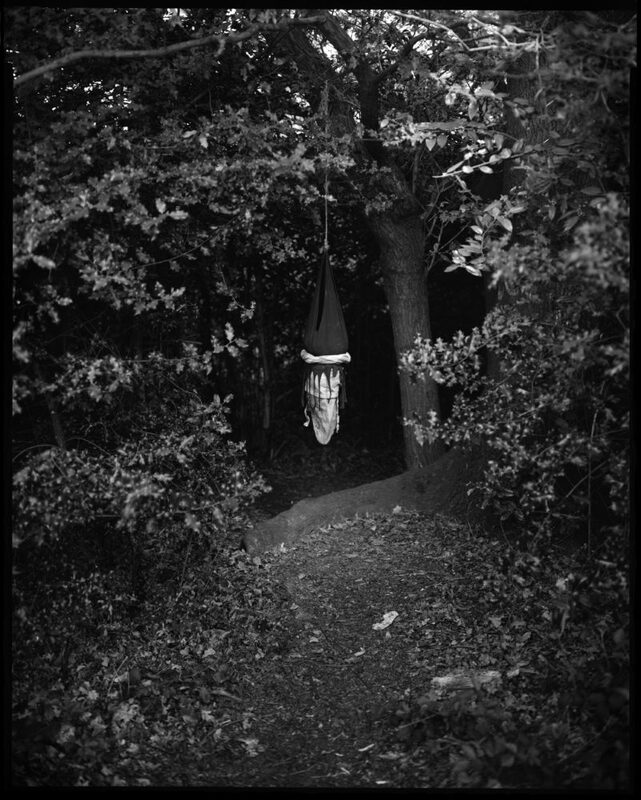

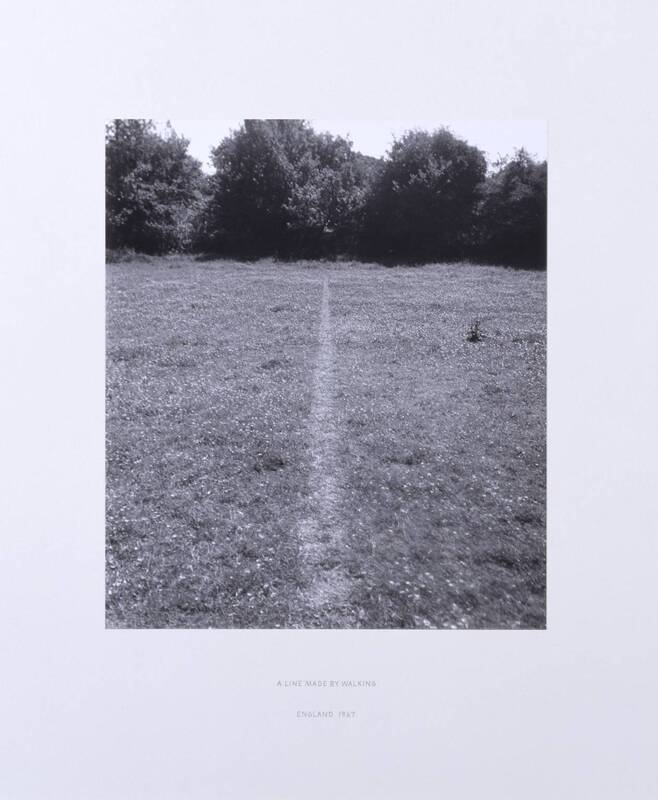

- How might you leave a trace of your presence; temporarily mark, disrupt, intervene, enhance or decorate the area? Pay attention to the various affordances and resistances of materials available - surface textures, colours, scale, solidity, viscosity etc. - how these might contrast or adapt with interaction, location or one another. Consider the following words as potential stimulus: Flatten, fold, mould, press, peel, shape, (re)arrange, organise, line-up, align; scratch, tear, rub, wipe, wash, mark; tread, trample, scuff, dig, unearth, reveal, conceal, turn-over. How might your response take inspiration from Prehistoric art, or the specific site chosen, and/or a related local, national or international issue?

Once complete, record your experiments with sketches, photographs or film, either immediately or over a subsequent period of time. Importantly, respect laws and others and then - based on the potential impact/benefit to the environment and community - decide if any marks you have made should be left or removed.

- How might you leave a trace of your presence; temporarily mark, disrupt, intervene, enhance or decorate the area? Pay attention to the various affordances and resistances of materials available - surface textures, colours, scale, solidity, viscosity etc. - how these might contrast or adapt with interaction, location or one another. Consider the following words as potential stimulus: Flatten, fold, mould, press, peel, shape, (re)arrange, organise, line-up, align; scratch, tear, rub, wipe, wash, mark; tread, trample, scuff, dig, unearth, reveal, conceal, turn-over. How might your response take inspiration from Prehistoric art, or the specific site chosen, and/or a related local, national or international issue?

The hands have an infinity of pleasure in them. the feel of things, textures, surfaces, rough things like cones and bark, smooth things like stalks and feathers and pebbles rounded by water, the scratchiness of lichen, the warmth of the sun, the sting of hail, the blunt blow of tumbling water, the flow of wind - NOTHING THAT i can touch or that touches me BUT has its own identity for the hand as much as for the eye. nAn shepHerd

- Take a long walk through a natural environment, perhaps a park, woodland or coastal path...with a range of containers to collect natural objects and resources along the way. This might include various leaves, berries, twigs, soil, stones, shells, mud, puddle, rain or sea water. Produce a series of studies of your collection using a variety of tools and techniques, for example:

- Natural History illustrations using a pencil or fine-liner - detailed, accurate, objective recordings as if in support of scientific study

- Large expressive responses with ink, using found sticks or adapted tools or pigments (e.g. earth and rain water).

Humans and Beasts

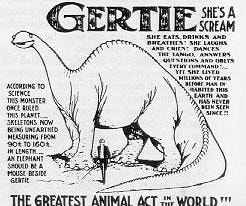

Dinosaurs and creatures from Prehistoric times, real, mythological or imagined, are a continual source of fascination, and not just for children. Jake and Dinos Chapman's 'Hell Sixty-Five Million Years BC' is a group of 74 dinosaurs and other prehistoric creatures made from materials (and in a manner) usually associated with Primary School art lessons. They have been scissored and pasted from toilet rolls, newspaper, cardboard packaging and poster paint. These brightly coloured monsters appear to have little technical skill or biological accuracy, yet they are funny, playful and visually striking as a collection. In addition, as is often the way with work by the Chapman Brothers, they have a sense of both the absurd and the apocalyptic; the work seems a mischievous response to contemporary fears regarding the future of the planet.

No excuses for the seeming childlike simplicity of this task: it provides an opportunity to experiment with various materials, forms and joining techniques, and also to make collaboratively on a large scale.

Dinosaurs and creatures from Prehistoric times, real, mythological or imagined, are a continual source of fascination, and not just for children. Jake and Dinos Chapman's 'Hell Sixty-Five Million Years BC' is a group of 74 dinosaurs and other prehistoric creatures made from materials (and in a manner) usually associated with Primary School art lessons. They have been scissored and pasted from toilet rolls, newspaper, cardboard packaging and poster paint. These brightly coloured monsters appear to have little technical skill or biological accuracy, yet they are funny, playful and visually striking as a collection. In addition, as is often the way with work by the Chapman Brothers, they have a sense of both the absurd and the apocalyptic; the work seems a mischievous response to contemporary fears regarding the future of the planet.

No excuses for the seeming childlike simplicity of this task: it provides an opportunity to experiment with various materials, forms and joining techniques, and also to make collaboratively on a large scale.

- Working in small groups using found and basic materials - cardboard, tubes, string, fabrics, piping, rolled newspaper, masking tape etc.: Create a large scale dinosaur, mythical or imagined creature. This might be a stand-by-itself, potentially life-size sculpture, or a costume constructed upon a member of your group. You might initially design this via drawing or collage, using images of various animals and creatures as a starting point. The creature might take inspiration from prehistory or present-day - consider contemporary issues, fears, machines, architecture, politicians, news...and this might inform shapes, forms, decoration.

- Experiment with scale and contrast, photographing the sculpture in various locations. Consider how these factors influence the humour, poignancy or surreal nature of the image.

- Use these sculptures or costumes as reference for a series of drawing exercises:

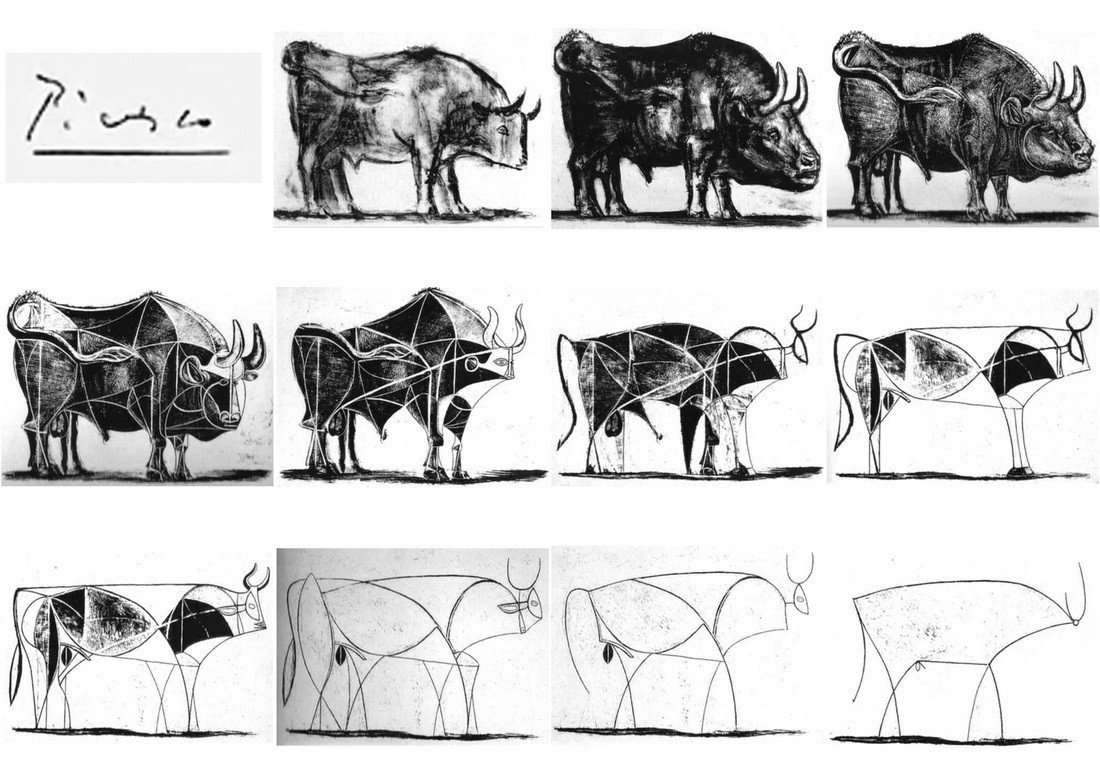

- Consider Picasso's Bull (Series), 1945. Experiment with line, simplifying and reducing, from realistic representation to the minimum marks required to suggest the forms.

- Use ink or cut-out paper to create shape-based responses - potentially also for arrangement as patterns

- Produce a detailed natural history illustration of your creature, as if you are an explorer recording a discovery in a notebook. Devise additional notes describing imagined behaviours.

- Design a small, simplified representation of your creature, using only a simple line drawing or shape. Using chalk, or a stencil and temporary spray paint, apply your design to various locations within the local environment - billboards, walls, paving stones etc. Consider unexpected and obscure locations and photograph the results.

- Experiment with scale and contrast, photographing the sculpture in various locations. Consider how these factors influence the humour, poignancy or surreal nature of the image.

PREHISTORY, in my view, continues up until the day before yesterday. It is part of our history, and it is made up of works of art. What counts in these works is not the technique; it is not the formal perfection; it is the feeling of empathy they arouse with the people who made them. MIQUEL BARCELó

FURTHER READING

The following texts have been chosen to promote wider contextual study. Students should consider the author's intentions, their chosen writing style, and how the texts combine research and historical facts alongside personal insights and opinions.

- A journey to the oldest cave paintings in the world, Jo Marchant, Smithsonian Magazine, 2016

- Gore Blimey - article on Chapman Brothers, Adrian Searle, Guardian, 2006

- One Step Beyond - article on Richard Long, Sean O'Hagan, Guardian, 2009

- Fat, felt and a fall to Earth: the making and myths of Joseph Beuys - Olivia Laing, 2016