TC#1

Mark making, often in the form of drawing, is considered to be the foundation of art – a way of thinking visually. It can be used for different purposes and is a powerful form of communication.

About the graphicOur Threshold Concepts for Art are accompanied with illustrations to aid their introduction. Each image contains a reoccurring graphic: a fingerprint in the shape of an artist's palette. In TC#1 this forms an eye drawing our attention, framed by a black circle which we recognise as a pair of glasses. The hand prints and dots are a nod to some of the earliest forms of mark making; the scribbles are representative of a more expressive type of mark making such as those made by Cy Twombly. The red lips (palette-shaped, again) are a playful link to this Cy Twombly related anecdote. Click the images below for further context.

|

“All art is but dirtying the paper delicately.”

John Ruskin

How might the artworks above connect to our TC#2 graphic? Follow the links to find out more. Consider the motivations for making these various marks.

WhAT DO I NEED TO KNOW?

- The definition of mark making is not fixed or limited to the materials that you find in the art cupboard. Marks - lines, dots, scratches, scribbles, patterns, textures, rubs, bumps, brushstrokes, pixels etc. - can be made in all sorts of ways, with an infinite amount of tools and techniques.

- When it comes to creating art, students can overly worry about the marks that they make. Art - making making - doesn't have to be a precious exercise. Marks can be used to produce hyper-realistic drawings (and this is fine), but they can also be more expressive, experimental, accidental, playful, abstract, energetic, symbolic, disruptive, misleading...

- One of the challenges for new art students is this: to worry less about creating impressive marks and to pay more attention to the qualities and subtleties of mark making. Think carefully, observe sensitively, and question often. How is this line weighted? How does this ink flow differently to that paint? How might that texture be re-created? What happens when I create marks without overly thinking - or without looking, even? What happens if I'm listening to music? Do marks have to be visual - for example, could a sound or a smell be considered as a type of mark?

- The meanings of marks are not fixed and are open to interpretation by individual viewers. How we read and interpret marks is shaped by our experiences , knowledge, understanding and intuition. Marks can be combined in infinite ways to draw our attention, with each addition having the potential to remind, provoke, suggest, challenge, express, celebrate, portray... Understanding the histories of art will improve your visual literacy.

Below is an introductory slideshow to encourage initial reflections and discussion:

Practical ideas for the classroom

Oodles of Noodles

Imagine trying to draw a plate of spaghetti or noodles, or a tangled ball of wool or string. Daunting? Or liberating, perhaps? Any attempt at accurate representation might seem futile; a less constrained approach might be considered an opportunity to respond more expressively ...

This exercise is a great way to get you thinking about ways of mark making, the purposes of drawing, and how best to employ the visual/formal elements of line, tone, texture, shape, colour, pattern, form, space. Here's a suggested sequence:

Imagine trying to draw a plate of spaghetti or noodles, or a tangled ball of wool or string. Daunting? Or liberating, perhaps? Any attempt at accurate representation might seem futile; a less constrained approach might be considered an opportunity to respond more expressively ...

This exercise is a great way to get you thinking about ways of mark making, the purposes of drawing, and how best to employ the visual/formal elements of line, tone, texture, shape, colour, pattern, form, space. Here's a suggested sequence:

- Prepare your tangled lines - cook some spaghetti; tangle a ball of string; confoodle your noodles...

- Produce a series of observational studies using a range of media (pencil, pens, brushes, dip pens, sticks, ink, chalk, charcoal etc.) working at a range of scales (highly intricate pencil studies; large and loose experiments - larger-than-a-small-house, for example. Go on, I dare you ...).

- Consider the skills required for accurate (photo-realistic) recording. How do these compare to those needed for looser, more expressive, less constrained responses? What gives a particular response more 'value' than another - not in financial terms, but in its visual, instinctive or intellectual appeal? How might your tangled reference be used to provoke further experimental, abstracted, or expressive responses?

Drawing Timelines

As we learn to make marks there are various stages of learning that we pass through, often without too much thought. Consider your own experiences - from early playful scribbles or grappling with perspective, to the frustrations and pressures of drawing accurately.

This link - a timeline of drawing development - will shed light on these stages of learning and assist with the task below:

Produce a series of self-portraits, one for each stage of the drawing timeline. You can employ a variety of strategies for this:

As we learn to make marks there are various stages of learning that we pass through, often without too much thought. Consider your own experiences - from early playful scribbles or grappling with perspective, to the frustrations and pressures of drawing accurately.

This link - a timeline of drawing development - will shed light on these stages of learning and assist with the task below:

Produce a series of self-portraits, one for each stage of the drawing timeline. You can employ a variety of strategies for this:

- The Scribbling Stage: Use your mouth or your cubital fossa (yep, I looked that up) to hold your pen or pencil.

- The Schematic Stage: Use your non-writing hand to grip your pen in fist - use basic, flat shapes and lines only with no suggestion of form.

- The Dawning Realism: Develop a more controlled, detailed version of your Schematic Stage self-portrait. Use your usual hand, but pay attention to the finer and more decorative details - textures for hair, patterns on clothes, freckles, shoe laces, teeth...

- The Pseudo-Naturalistic Stage: Remember those first attempts at one-point perspective, or smudging your pencil in an attempt to make a drawing look 'more real'? Try to recreate these attempts. They are often a little more heavy-handed in line quality with key features overly-outlined.

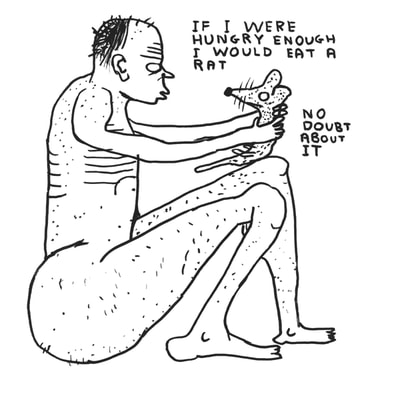

The above images, top row, show various stages of drawing development in children. The four images below these are by established artists.

Why are so many artists drawn to techniques and approaches that may, at first glance, seem overly simple or child-like?

Which words best describe the similarities or the differences between the two layers of images?

Mark making as Performance

Mark making is a physical activity: we grasp a tool, apply pressure to a surface and move our hands. But of course there is more to the experience than this. As we create art we are constantly moving, looking, thinking and engaging emotionally. Our bodies are active and endorphins abound. The larger the scale, the more physical the act becomes. Sweeping arm movements can add new energy; mark making becomes an act of physical expression.

Mark making is a physical activity: we grasp a tool, apply pressure to a surface and move our hands. But of course there is more to the experience than this. As we create art we are constantly moving, looking, thinking and engaging emotionally. Our bodies are active and endorphins abound. The larger the scale, the more physical the act becomes. Sweeping arm movements can add new energy; mark making becomes an act of physical expression.

- Watch the two short videos below. The first is an introduction to Performance Art, the second shows a range of live drawing performances. (Note: this does contain some nudity from 9:51 to 10.15).

|

|

|

Jackson Pollock famously stated: "I don't paint nature, I am nature". His paintings and the physical act of mark making - rhythmically moving about his canvas, pouring, dripping, painting with gesture - are inseparable. Is mark making a kind of performance?

Consider the physicality of different ways of working with reference to the examples in the videos (gestures, dances, performances, sound-making, interactions etc.). How do these compare to your own experiences of mark making? How might you explore mark making in new ways?

- Devise a collaborative performance that results in marks being left as evidence. A starting point might be a recorded conversation, a music track, or a news article. Alternatively the work might be a spontaneous visual conversation with participants making marks in silent response to one another.

“We who draw do so not only to make something visible to others, but also to accompany something invisible to its incalculable destination.”

John Berger

FURTHER READING

The following texts have been chosen to promote wider contextual study. Students should consider the author's intentions, their chosen writing style, and how the texts combine research and historical facts alongside personal insights and opinions.

- A Journey to the Oldest Cave Paintings in the World, Jo Merchant, Smithsonian Magazine, 2016

- Through the eyes of a child Christopher Turner, Tate Etc., 2010

- The deliberate accident in art Christopher Turner, Tate Etc., 2011

- A Bigger Splash: did performance art change painting? Adrian Searle, The Guardian, 2012

- Cy Twombly - blood-soaked coronation for a misunderstood master Jonathan Jones, The Guardian, 2016

- Drawing to learn, learning to draw, Eilleen Adams, NSEAD resources, 2013