TC#3Works of art consist of formal and visual elements (such as line, shape, form, pattern, texture, colour etc.). These elements combine to communicate in many ways, often suggestive of histories and traditions.

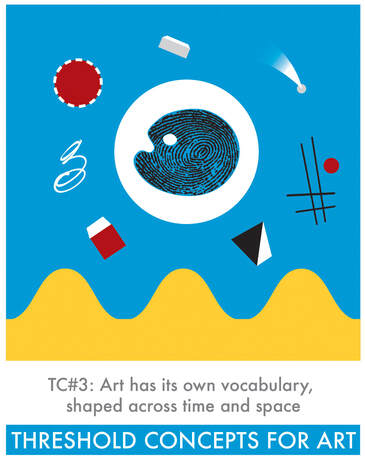

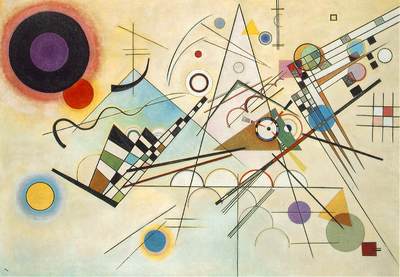

About the graphicOur Threshold Concepts for Art are accompanied with illustrations to aid their introduction. Each image contains a reoccurring graphic: a fingerprint in the shape of an artist's palette. In TC#3 this sits central, an island in space (or an eyeball, even) orbited with some rather shapely suggestions: a polyhedron (a pyramid, perhaps?), a scribble, a cube, circles (moons, a sun, or something else?), waveforms... But there may be more - an essence of Joan Miro, a dash of Kandinsky, a Carl Andre brick, perhaps? The simplest combination of visual elements – whether intending to reference histories and traditions or not – has the potential to evoke connections and meanings, subject to our own personal experiences, knowledge, understanding and intuition.

|

"Art is a language, an instrument of knowledge, an instrument of communication."

Jean Dubuffet

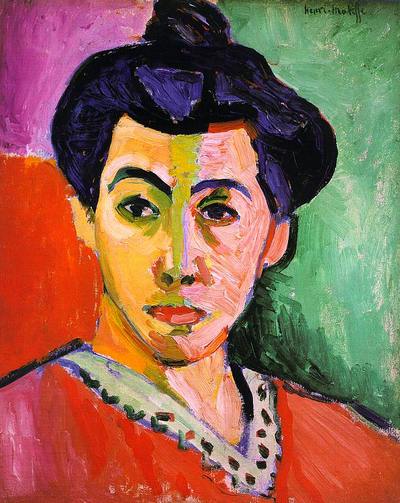

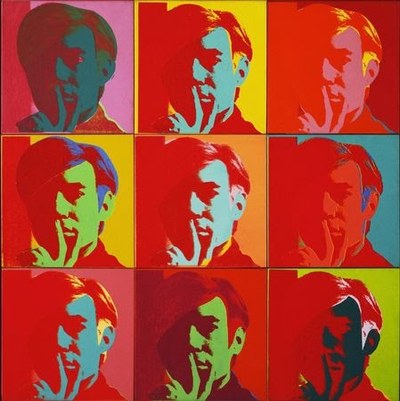

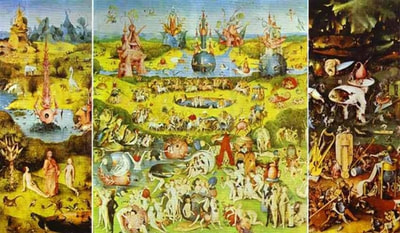

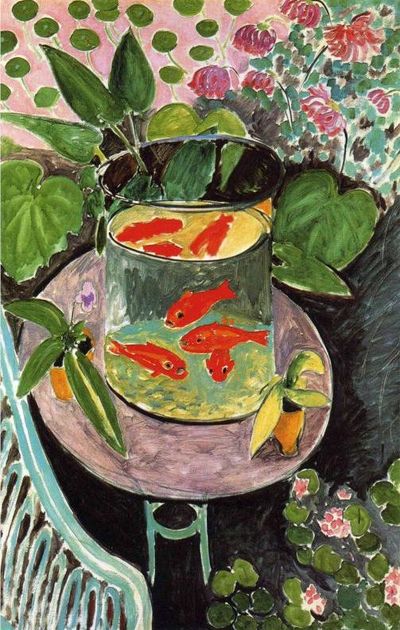

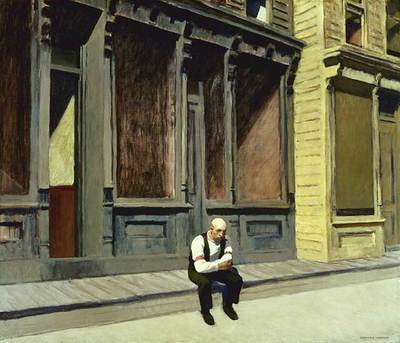

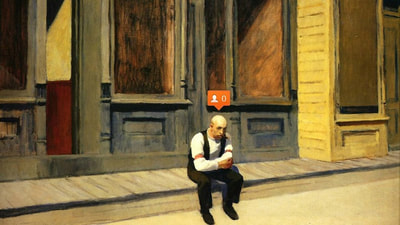

How might the artworks above connect to our TC#3 graphic? Alternatively, what connections might be made between these 3 different images? Do these 3 artworks share common vocabulary? Which example of work communicates the most to you? What is its appeal and why?

WhAT DO I NEED TO KNOW?

- Works of art consist of formal and visual elements. Simply put, this refers to the information that we see. Most teachers of art agree that these elements include: Line, Tone (or Value), Shape, Colour, Texture, Form and Space. To describe the arrangement - the composition - of these elements, other words also become important: Pattern, Rhythm, Contrast, Harmony, Balance, Scale, Proportion, Tension, Flow are just some examples. Importantly, an appreciation of art and art-making is not tied to an ability to articulate the experience in words; art communicates in many ways.

- Our interpretations of art are subject to change and are shaped (and re-shaped) over time and space. For example, new knowledge and experience gained over time may reveal previously unconsidered connections; our physical encounters within the world, for example, a trip down a river, the sensation of flying, or perhaps experiencing the smell of sulphur might bring new sensitivities to experiencing certain artworks.

- Artworks exist as evidence of action from within a particular time and space. However, viewers rarely encounter an artwork in the same time and space of its creation, and this can greatly influence how the work is received. Some artworks, and artists (individually or collectively), gain the status, recognition or support to eventually become a part of 'art history'. The histories of art - the stories we share about art and artists - are also subject to change across time and space.

- The formal and visual elements within an artwork combine to communicate in many ways, often suggestive of histories and traditions. Artists often play with these possibilities, frequently with inspiration and respect, but also in more critical and subversive ways.

Below is an introductory slideshow to encourage initial reflections and discussion:

Practical ideas for the classroom

When artworks collide

What happens when two artworks are placed together by chance? Do new interpretations, insights or ideas emerge? And then, what happens when we begin to describe the potential connections? How do the words that we choose bring to light (or restrict) new possibilities and ways of thinking? Below are two sets of randomly paired artworks which have had various words placed between them:

What happens when two artworks are placed together by chance? Do new interpretations, insights or ideas emerge? And then, what happens when we begin to describe the potential connections? How do the words that we choose bring to light (or restrict) new possibilities and ways of thinking? Below are two sets of randomly paired artworks which have had various words placed between them:

It's interesting to consider how the images become connected in various ways via the words. Below is a suggested lesson sequence for this activity:

- Place a wide range of printed examples of artworks face down upon the table. Use diverse works from across time and place.

- Take turns to randomly select two works to place alongside each other.

- Firstly, write down the visual element that most obviously connects the two examples. Pay attention to the speed with which this conclusion is drawn. Is there an obvious answer, or is this debatable?

- Secondly, with careful consideration, choose one word that can be placed between the two artworks to provoke new possibilities. Play with the possibilities of language: Which words create the most intrigue? Do words that simply describe seem to limit deeper reflection?

- Thirdly, what happens if you pick a word by chance from a dictionary? Or alternatively, devise a list of potential words (random or carefully considered) for selection alongside the images. Here are some suggestions: turmoil; typical; hilarious; Pop!; bicycle; melon; future; dreaming; STOP!; pray; promise; look; LOOK!...

- What if a word is placed as a caption below one image only? How about within a strategically (or randomly) placed speech bubble? Finally, as an alternative to writing words, what happens if the word is repeated verbally whilst looking at the two images? Could this activity become a form of performance?

Exchanging styles and ideas

Certain formal and visual elements are often closely associated with particular art movements or periods from within art history. What happens when we play with these expectations?

Certain formal and visual elements are often closely associated with particular art movements or periods from within art history. What happens when we play with these expectations?

The Fauves ("wild beasts") were a loosely allied group of French painters (circa 1905-1910) that included Henri Matisse and André Derain. These artists shared the use of pure color as a means of intensifying emotion and exploring light and space. Pop art is an art movement that emerged in the 1950s in America and Britain, drawing inspiration from sources in popular culture, not least the bright contrasting colours of new print and film technologies increasingly evident in packaging, advertising, comic books and movies.

Spanning a longer period of time, and with wider immediate appeal than the Fauvists, the Pop Art movement certainly generated the more diverse outcomes - from paintings and sculptures to experimental films, performances and installations. However, it is possible to see distinct similarities between the two movements, as apparent in the examples above (Fauvist examples on the top row, Pop Art examples below).

To extend on this further you might create a list of various art movements (Impressionism, Futurism, Cubism, Surrealism and so on); a list of potential subject matter (a portrait of an elderly person, a shoe, a goat, a toolbox...) and perhaps a list of materials or techniques (collage, chalk and charcoal, sound installation, card construction, modelling clay, animation etc.). These can then be drawn at random to generate instructions for experimenting, for example: Produce an Impressionist style response to a goat using only card construction; Produce a Surrealist sound installation in response to a shoe.

Below are some examples of artworks that have taken inspiration from previous artists and art movements. Follow the links to find out more information.

Spanning a longer period of time, and with wider immediate appeal than the Fauvists, the Pop Art movement certainly generated the more diverse outcomes - from paintings and sculptures to experimental films, performances and installations. However, it is possible to see distinct similarities between the two movements, as apparent in the examples above (Fauvist examples on the top row, Pop Art examples below).

- How might the similarities between (and within) the two rows of examples, above, be best explained? Which words become the most useful to do this? What about the differences?

- What happens when you experiment with exchanging styles and techniques or ideas and intentions? For example, chose one of the following as a starting point for practical exploration:

- Produce a Fauvist-inspired painting of a Pop Art-inspired theme.

- Produce a Pop-Art-inspired artwork (e.g. a painting, sculpture or film) but using a Fauvist-inspired landscape as a starting point.

- Produce a Fauvist-inspired painting of a Pop Art-inspired theme.

To extend on this further you might create a list of various art movements (Impressionism, Futurism, Cubism, Surrealism and so on); a list of potential subject matter (a portrait of an elderly person, a shoe, a goat, a toolbox...) and perhaps a list of materials or techniques (collage, chalk and charcoal, sound installation, card construction, modelling clay, animation etc.). These can then be drawn at random to generate instructions for experimenting, for example: Produce an Impressionist style response to a goat using only card construction; Produce a Surrealist sound installation in response to a shoe.

Below are some examples of artworks that have taken inspiration from previous artists and art movements. Follow the links to find out more information.

Here are some further prompts to initiate discussions and practical work, with reference to the examples above and below:

- Which artworks seem the most obviously connected? How is this achieved? Consider the dominant formal and visual elements, but also the close similarities between subject matter, composition, media and techniques.

- Is it possible to always tell which artworks were created first? Which pairings from above or below appear to have the greatest amount of years between each creation? Why do you think this?

- Why might an artist choose to create art that is a direct (or indirect) reference to the work of someone else? Are such responses always motivated by respect and admiration?

The examples above show deliberate intent to produce art in response to the work of others, however, the choice of visual and formal elements, and materials and techniques, is often quite different. Why do you think this is? How does an alternative approach expose the gaps between the works - how has the making of art, the ideas of artists, or even the world itself, changed over time?

Forming an Art Movement

We have a tendency to group artists and artworks by 'art movements'. This is particularly true of modern art (which broadly refers to a period of rapid development in art from the 1860s to the 1970s). Many art movements, for example, Futurism, Dada and Surrealism, have evolved through artists forming like-minded alliances, often setting out their collective intentions or 'rules' within an art manifesto. However, some art movements have evolved over time (or overnight, even) through someone (often gallery owners, journalists or art critics, even) grouping together particular artists, and not always with good intentions. For example, Impressionism (impressionistic, not accurate) and Fauvism ('wild beasts') were initially satirical, derogatory labels assigned by unimpressed critics.

Consider the questions below prior to forming your own art movement with peers:

Forming an Art Movement

We have a tendency to group artists and artworks by 'art movements'. This is particularly true of modern art (which broadly refers to a period of rapid development in art from the 1860s to the 1970s). Many art movements, for example, Futurism, Dada and Surrealism, have evolved through artists forming like-minded alliances, often setting out their collective intentions or 'rules' within an art manifesto. However, some art movements have evolved over time (or overnight, even) through someone (often gallery owners, journalists or art critics, even) grouping together particular artists, and not always with good intentions. For example, Impressionism (impressionistic, not accurate) and Fauvism ('wild beasts') were initially satirical, derogatory labels assigned by unimpressed critics.

Consider the questions below prior to forming your own art movement with peers:

- What kind of artworks are you most drawn to and why? Which formal and visual elements do you tend to pay most attention to in your own work - is it all about surface, texture and tactile experience, or is colour everything to you? Do you tend to sculpt, construct or model, or are you happiest with a pencil or stick of charcoal in your hand?

- Which art movement would you most like to be associated with, and why? And who within your class has similar interests or ways of working to you?

- Is there an art movement that you wouldn't want to be associated with? For some artists, associations with particular movements or styles have been less welcome. Frida Kahlo is one example: "They thought I was a Surrealist, but I wasn't. I never painted dreams. I painted my own reality.”

- If you were to form your own art movement, individually or as a group, what distinct visual vocabulary would your work contain? And how about a written manifesto that sets out your aims and intentions - which words would be most important for this?

“Making art is a political act. I’ve always believed that. It wrestles with beauty, fear, emotion. It doesn’t have a verbal language attached so it becomes a game. It’s feral in its existence. And we have to fathom it.”

PHYLLIDA BARLOW

FURTHER READING

The following texts have been chosen to promote wider contextual study. Students should consider the author's intentions, their chosen writing style, and how the texts combine research and historical facts alongside personal insights and opinions.

- A user's guide to art speak, Andy Beckett, The Guardian, 2013

- Let's ditch the artspeak and artybollocks, Susan Jones, The Guardian, 2015

- Two masters, one friendship: The story of Matisse and Picasso, Flavia Frigeri, Tate resources, 2014

- How John Berger changed our way of seeing art, Yasmin Gunaratnam and Vikki Bell, The Conversation, 2017

- How to start a movement, Tate resource by gal-dem