PRIMARY RESOURCE

|

The business of art is to bring something into existence ARISTOTLE

IN PICTURES - ANCIENT FIGURES & FORMS

The images above show a variety of ways of recording the human form. These are all examples from the regions of Ancient Mesopotamia and Greece. Consider the questions below prior to reading further.

- Which of these is the oldest artwork, and what makes you think this? Is it possible for you to put them in order from the oldest to the most recent (which would still be very old!)? Is it helpful, important or even necessary to organise artworks historically (and chronologically)?

- How do you think they were created? What tools or techniques may have been used? Were they made by artists, and if so, were they asked or ordered to make these, or were they made for personal reasons?

- Why do you think they were created? Do they have a particular purpose or function - a reason for their creation?

- What words help to describe their visual and material properties? Use the list of words below to help with this.

Further notes:

- Image 1: Terracotta figurine of a standing nude woman, believed to be a fertility charm. 1000-500 BCE

- Image 2: A low relief - this is the name given to a raised surface sculpture, rather than fully 3 dimensional. This depicts a supernatural protective figure and a mortal Assyrian courtier. The panel decorated the palace of an Assyrian king and celebrated his power. 883–859 B.C.

- Image 3: Olympic runners depicted on an ancient Greek vase, given as a prize in the Panathenaea, circa 525 BCE

- Image 4: Marble statue of a kouros - a popular ancient form of sculpture that ceremonially depicts a young man, stepping forward into adulthood, originally based on the greek god, Apollo. 590–580 B.C.

SHIFTING SHAPES, COLOURs, FORMS...

Throughout history, art has always been subject to change. The role and status of artists has varied greatly over time, as have the styles, media and techniques that they use. Today, artists are often considered original thinkers and independent spirits, however, in Ancient Greece (for example), artists would have been considered as crafts or tradespeople, valued for their technical skill and ability to conform to an established style rather than express their own ideas.

Look carefully at the two images below and consider their similarities and differences.

Look carefully at the two images below and consider their similarities and differences.

Image 1: 'The Peplos Kore' is one of the most well-known examples of Archaic Greek art. The white marble statue was made around 530 BC . Originally, it was colourfully painted but has since faded with time. The image alongside shows a re-creation of how it may have appeared.

Image 2: Ancient Greek Terracotta pelike (wine jar), ca. 510 B.C. depicting Olympic runners.

Art from Ancient Greece is often classified within different periods. The image on the left shows a sculpture from the Archaic Period, inspired by Egyptian sculpture. Compare this to the painted illustration on the right, produced in a style more associated with the Classical Period. Which words, below, might help you to explain the differences in these artworks?

RIGID, FIXED, STILL, LINEAR, SOLID, FORM, FLAT, SIMPLIFIED, EXAGGERATED, ABSTRACTED, FLATTENED, SHAPE-BASED, MOTION, MOVEMENT, DYNAMIC, TENSION, RHYTHM

Image 2: Ancient Greek Terracotta pelike (wine jar), ca. 510 B.C. depicting Olympic runners.

Art from Ancient Greece is often classified within different periods. The image on the left shows a sculpture from the Archaic Period, inspired by Egyptian sculpture. Compare this to the painted illustration on the right, produced in a style more associated with the Classical Period. Which words, below, might help you to explain the differences in these artworks?

RIGID, FIXED, STILL, LINEAR, SOLID, FORM, FLAT, SIMPLIFIED, EXAGGERATED, ABSTRACTED, FLATTENED, SHAPE-BASED, MOTION, MOVEMENT, DYNAMIC, TENSION, RHYTHM

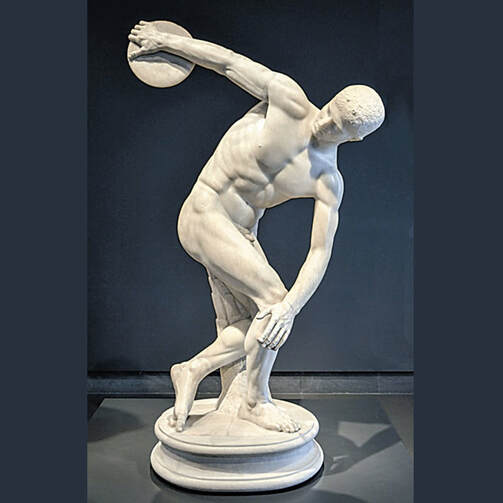

As seen in the examples (above left), Greek art from the Archaic period was very rigid, still and upright. Artworks from the Classical period changed from these simplified and symbolic statues to more dynamic and detailed forms. Statues of gods, athletes and celebrated others took on 'ideal' human forms. Great attention was paid to proportion, rhythm and balance.

POTENTIAL ACTIVITIESThe Discobolus of Myron (discus thrower), is a Greek sculpture completed at the start of the Classical period at around 460–450 BC. The sculpture depicts a youthful male athlete throwing a discus. The original Greek bronze is lost but the work is known through numerous Roman copies.

|

|

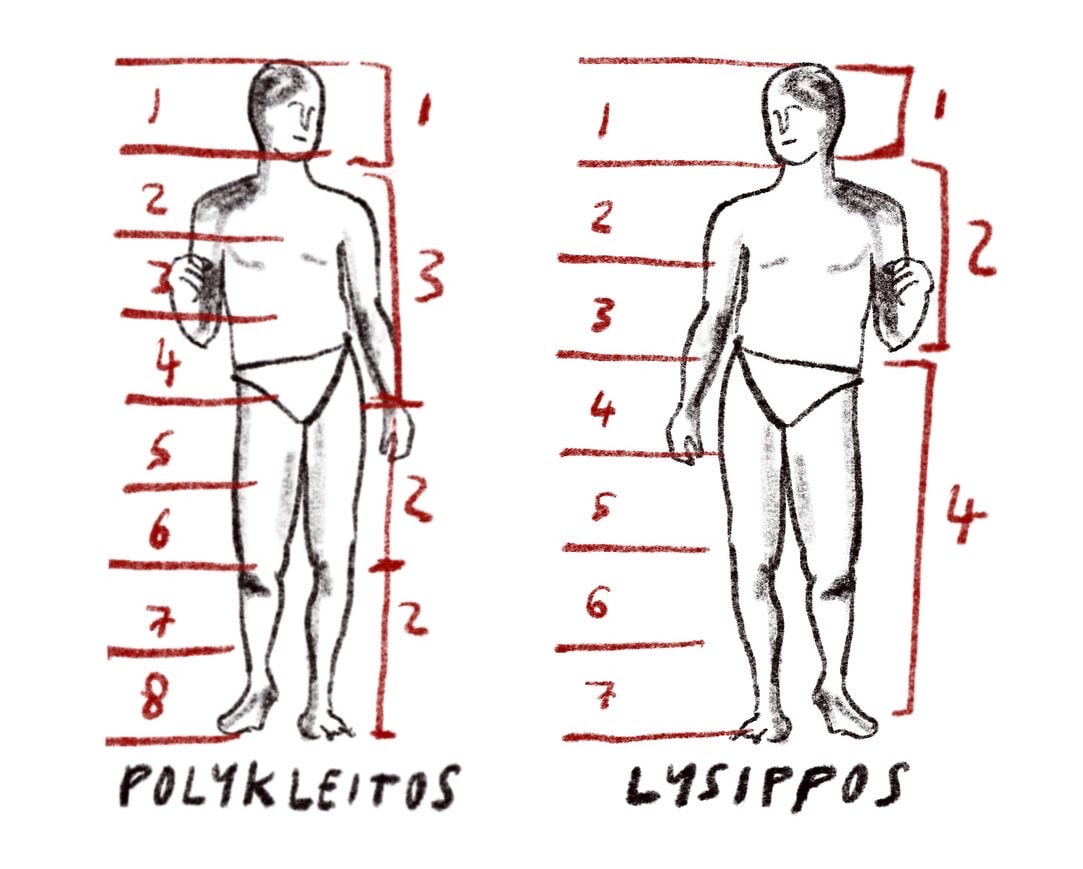

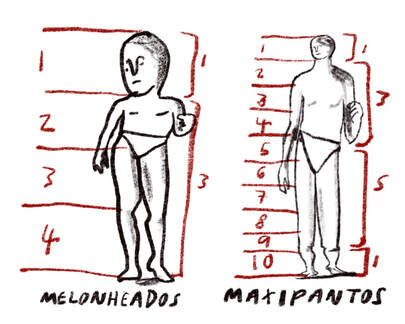

Ancient Egyptians and, consequently, Ancient Greeks devised strict rules for drawing and sculpting human proportions. The word 'proportion' refers to the size of something in relation to something else, such as one body part in relation to another.

A system for measuring proportions is often referred to as a 'canon' and, for the Egyptians and Greeks, these ancient systems set out certain ideals of beauty. Of course, the idea of beauty is subjective and ever-changing. There is no such thing as an 'ideal' proportion and humans, delightfully, come in all shapes and sizes. The illustration on the right shows two, slightly different canons of proportion according to two Ancient Greek sculptors, Polykleitos and Lysippos. Simply put, these show the head as one measurement of proportion. The body is then broken down by this measure, for example, Lysippos's canon shows 4 heads would fit into the feet, legs and waist, 2 heads make up the distance between waist to shoulder. |

|

In ancient times, artists would have been taught to strictly follow certain canons of proportion. However, when drawing this can also be misleading. Proportions are distorted as soon as a figure moves or is viewed from another angle rather than direct eye level. More playfully, as Threshold Concept 4 reminds us, present-day artists often abuse and ignore traditions to challenge conventions.

|

Incredibly and impressively, classical sculptures were (and still are) carved out of large blocks of stone or marble. The process would have been (and still is) highly skilled and physical, and also expensive and time-consuming. Apprentice artists would have worked under a master artist and would only have been trusted to work at a larger scale after sufficient time and training.

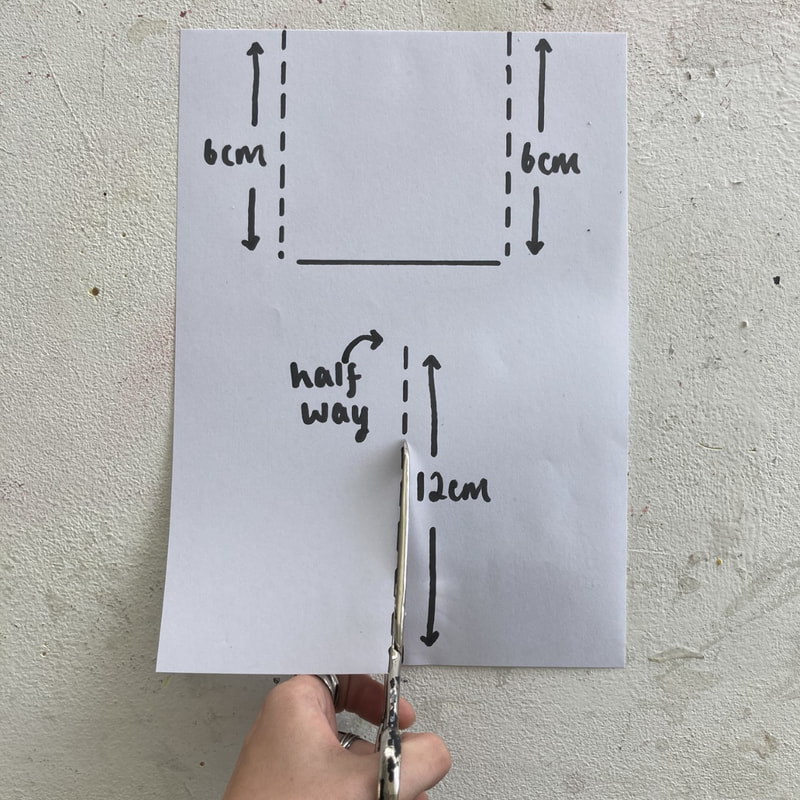

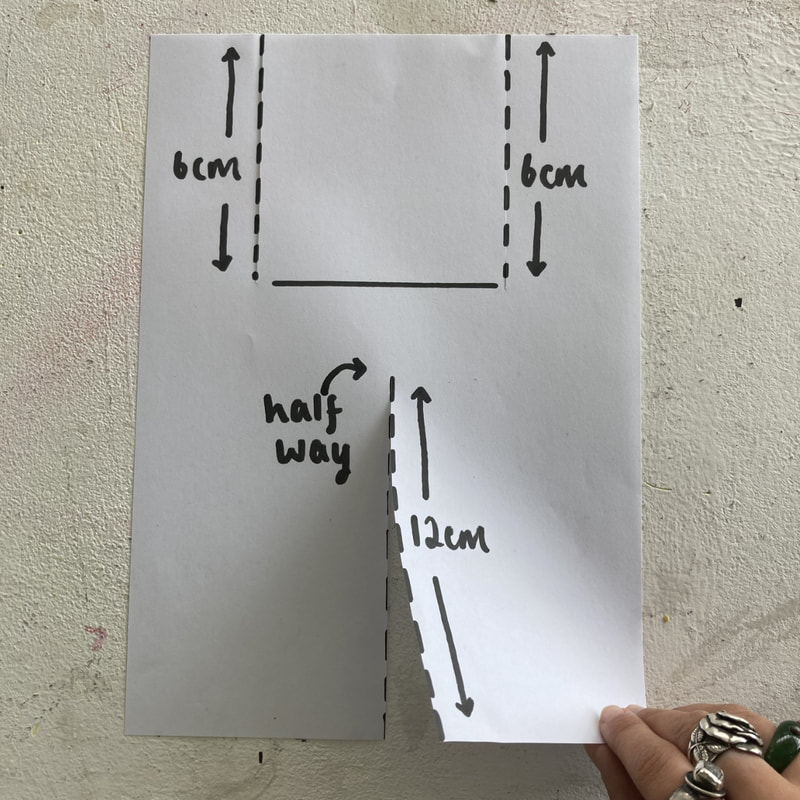

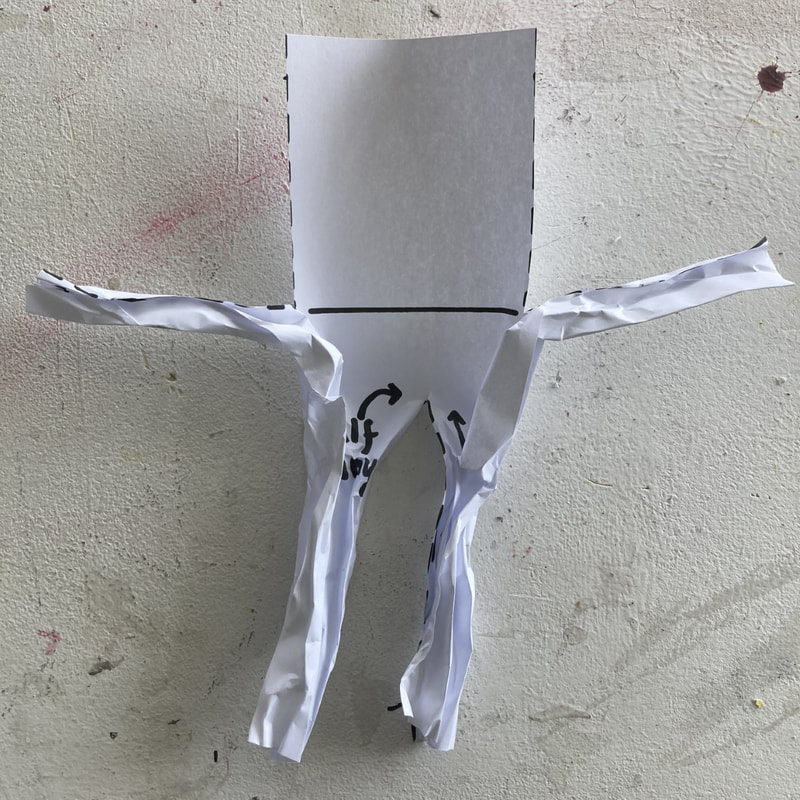

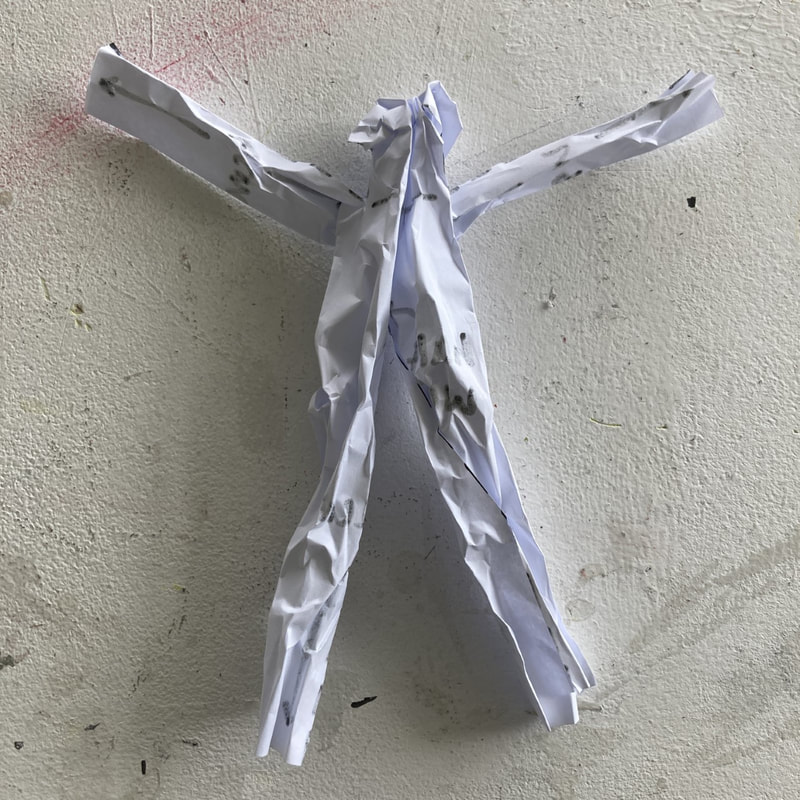

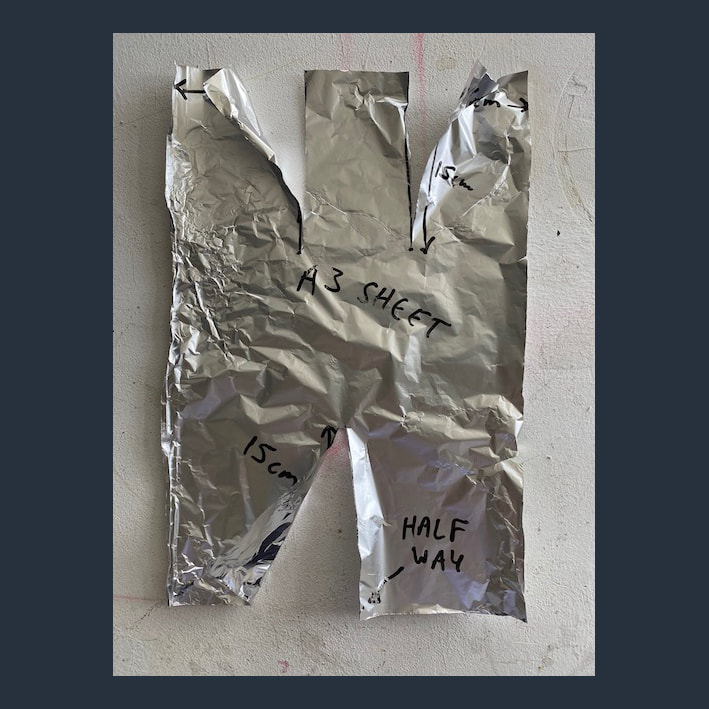

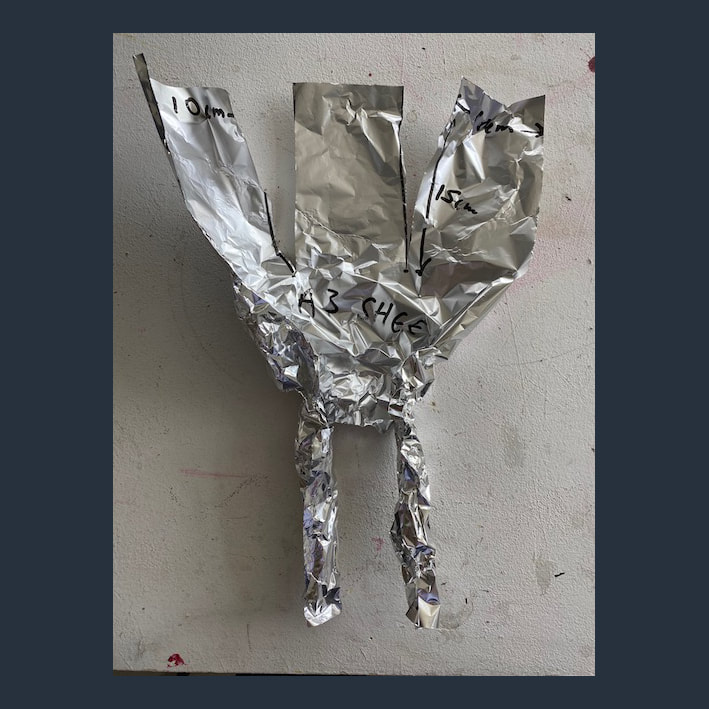

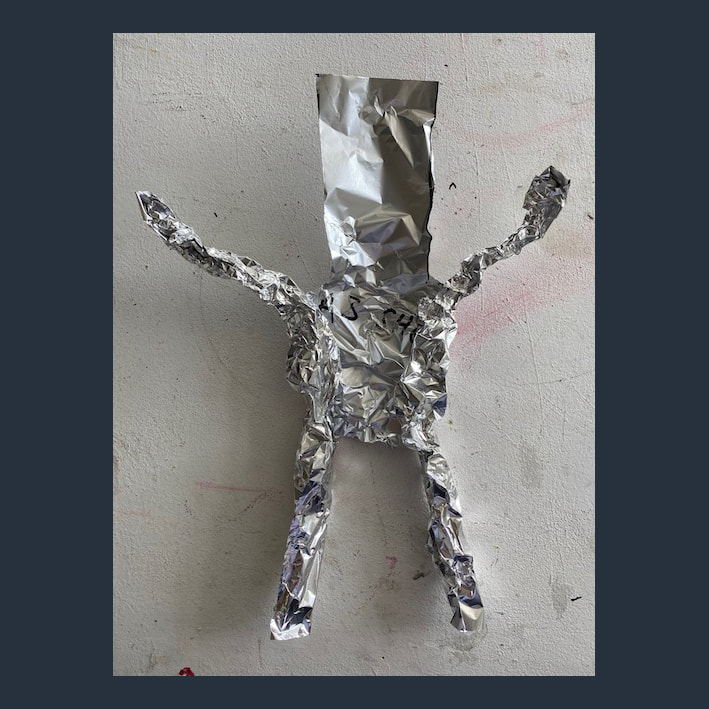

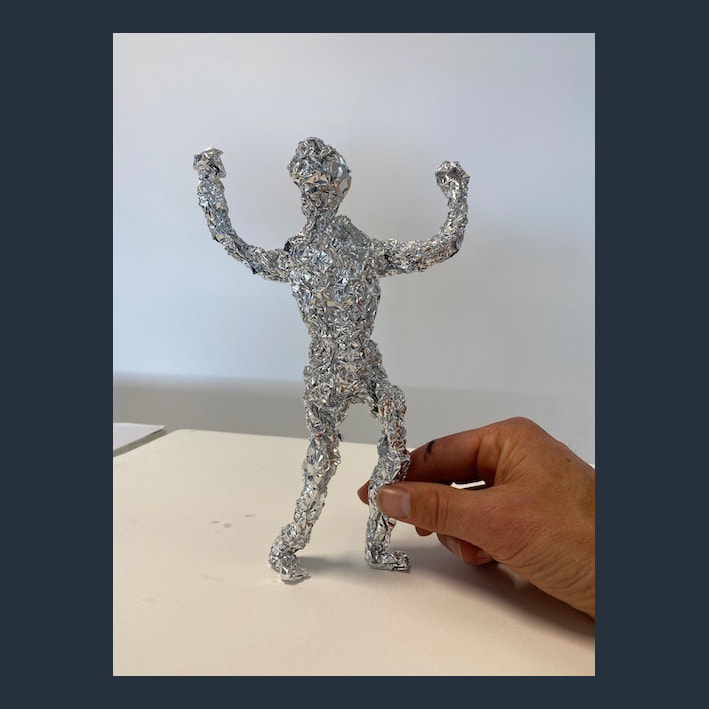

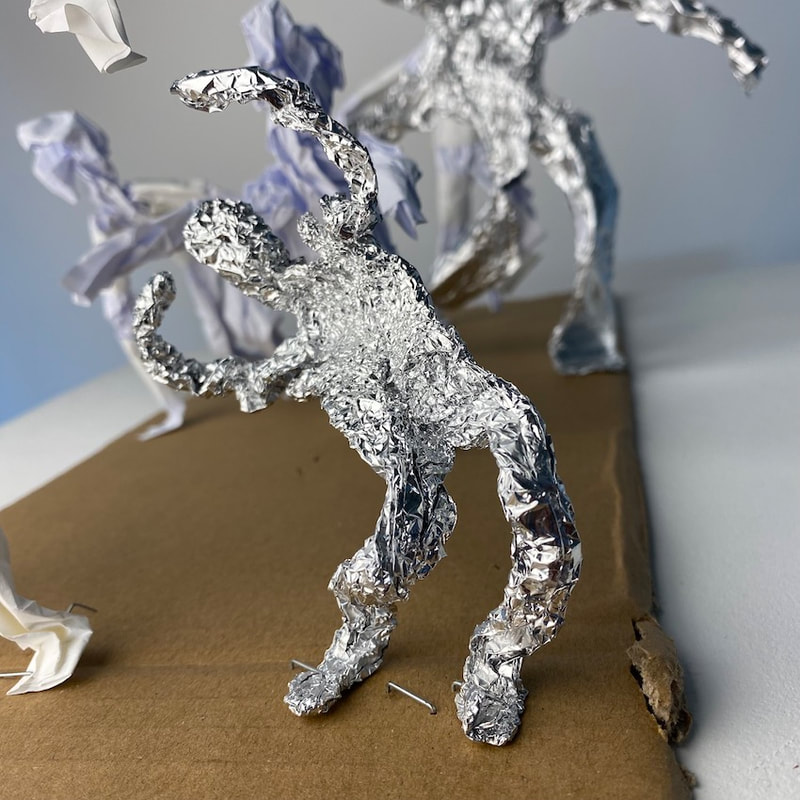

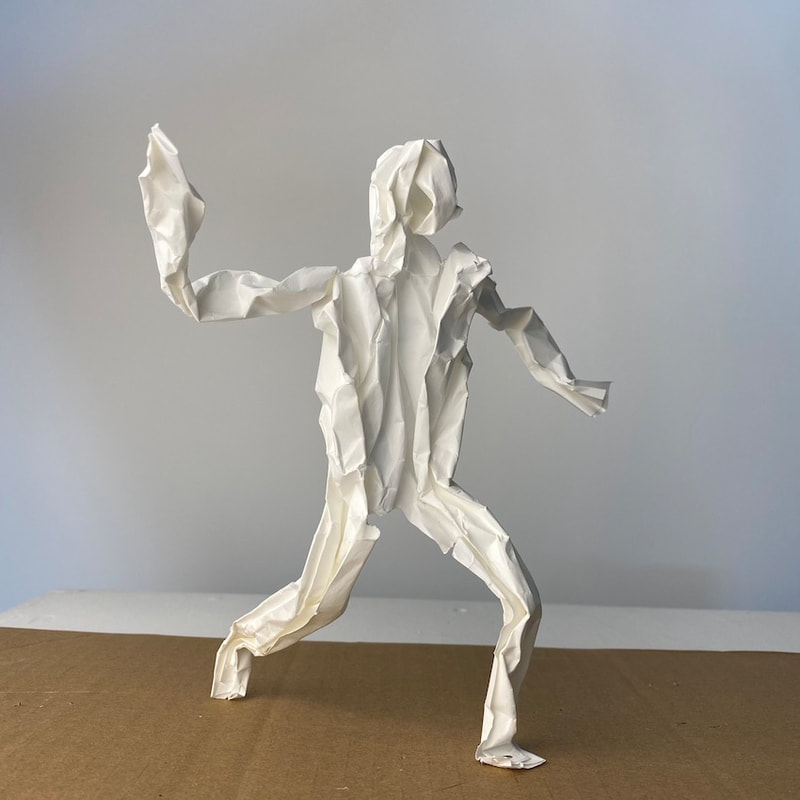

- In contrast to the cost, time and training required to sculpt a human form in stone or marble, the exercise below invites you to make your own figure using a sheet of paper. Follow the images stage-by-stage. You might wish to experiment with alternative scales and measurements to see how it alters proportions. You might also try different textured surfaces to test the resistances and affordances of the paper/material - what the paper might allow (afford) you to do or stop you from doing (resist) e.g. how it folds, creases, tears, rolls.

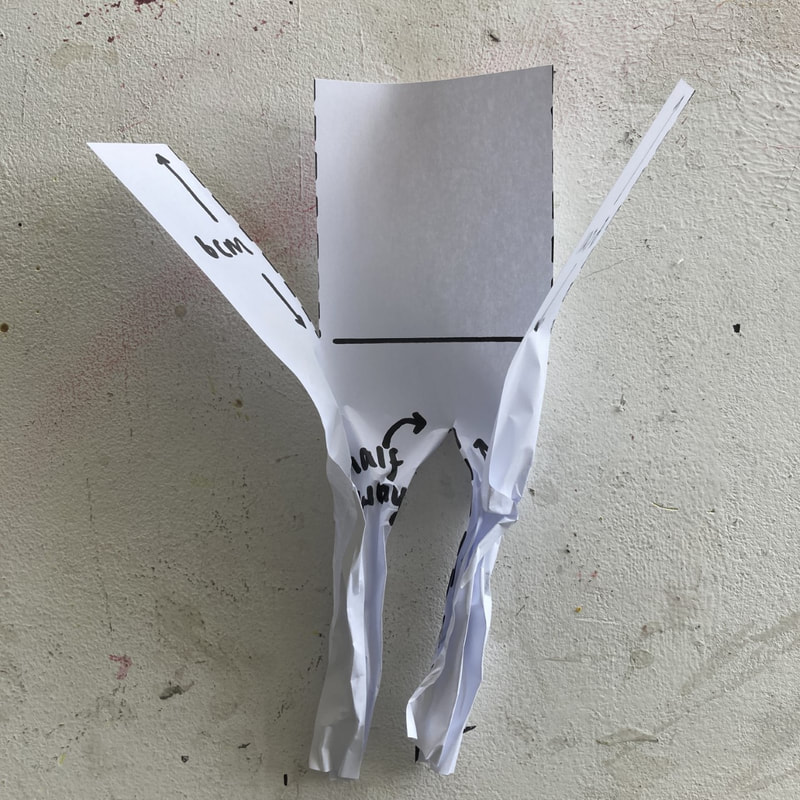

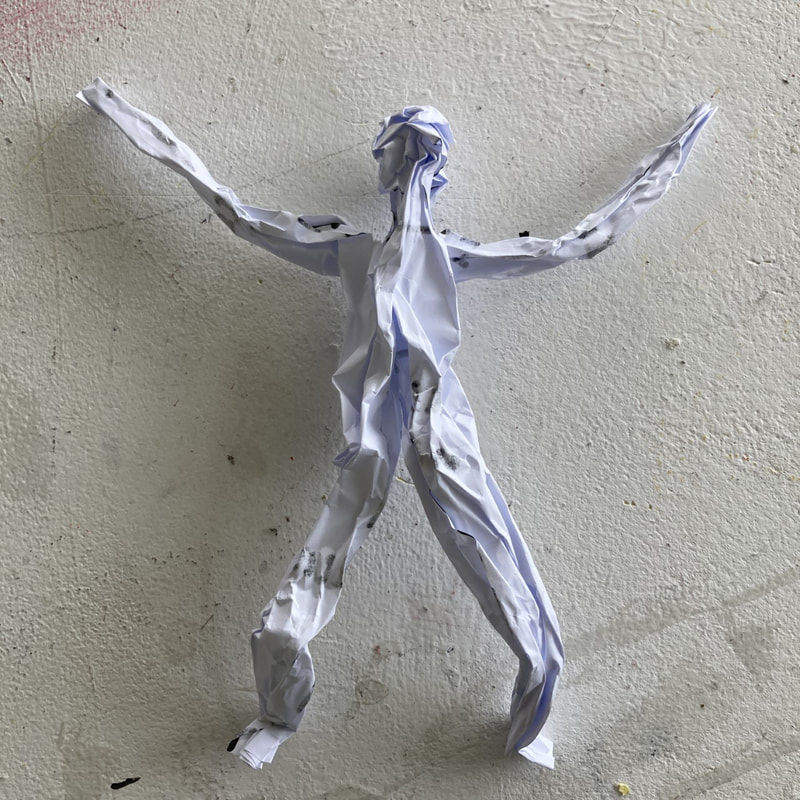

The images above show how to construct a figure with an A4 sheet of paper. The challenge here is to embrace the limitations of the paper and via touch and experimentation 'push and pull' it into the form you want. The paper will inevitably crease so consider how the creases and folds might help suggest muscles and forms.

|

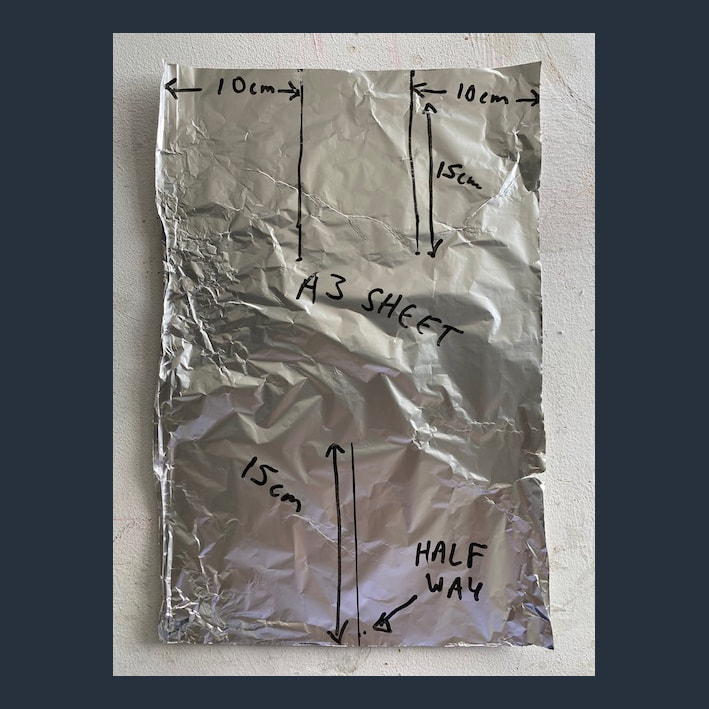

The sequence above uses an A3 sized sheet of tin foil. This is not as environmentally friendly as paper which can be more easily recycled. It is also more expensive. However, the foil does have different properties to paper - different affordances and resistances, alongside surface qualities - and can be manipulated more precisely.

The quick animation, left, was made by photographing the figure with a fixed camera (a phone propped up and masking taped in position to keep it still). The figure was photographed after each movement of being gradually folded down and screwed up. The images were then put in reverse using a basic stop motion animation app. Perhaps part of the value of these paper sculptures for artists is their unpredictability - the resistance they put up when you attempt to fold them into a particular position. The paper figures don't always behave how you want, and this can create unexpected contortions and abstractions. These imperfections and fragilities can still make students think hard about proportions and how the human form should or shouldn't be, yet they also provide an interesting contrast to the Ancient Greek quest for solid perfection. |